CAPREIT: Betting on the Canadian Century

Insatiable demand for housing meets chronically insufficient supply, thereby creating the ultimate scarce asset: an affordable and practical place to live in the fastest growing developed country.

Generally, investing into real estate can pay off two ways: Generating income or riding an appreciating asset. To assess whether it makes sense to invest into a real estate market, we must therefore assess whether…

Demand for rent is strong.

Supply for rent is not excessive.

There is upside in home prices and rents.

In my opinion, all of that is true for Canadian residential real estate today and that makes Canadian Apartment Properties REIT (CAPREIT) a promising investment. In this report, I will explain why. As outlined in the valuation section in the last section, I see more than 40% immediate valuation upside that will keep compounding.

Company Background

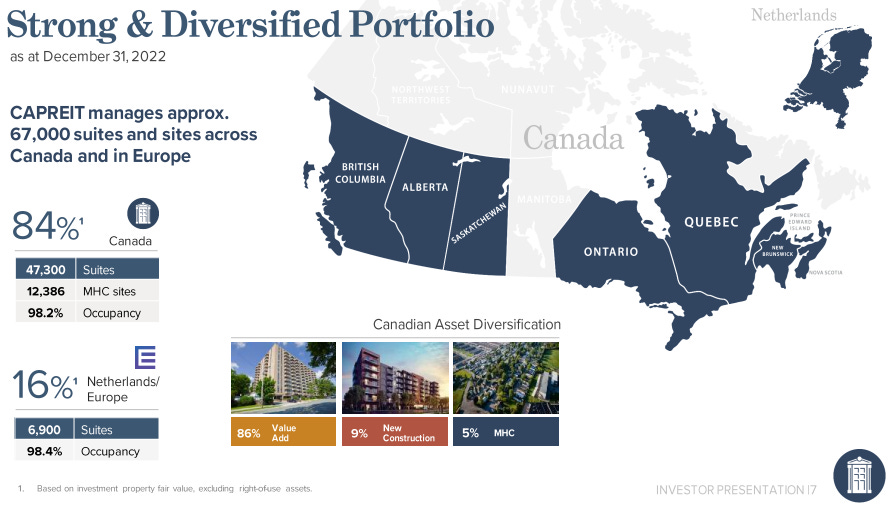

First some background on the company we’re looking at here. CAPREIT was founded in 1996 and listed in 1997. It’s the largest Canadian residential REIT with a $17bn property portfolio.

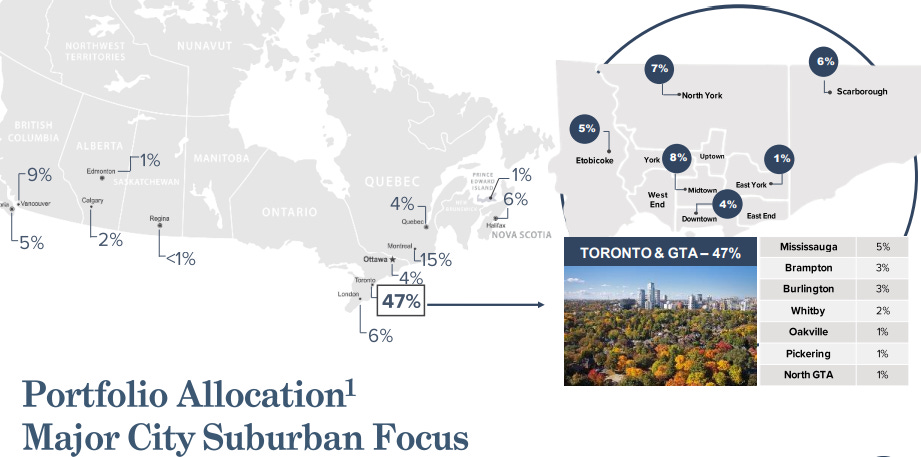

They have properties all over Canada (and oddly some in the Netherlands), with a focus on Toronto.

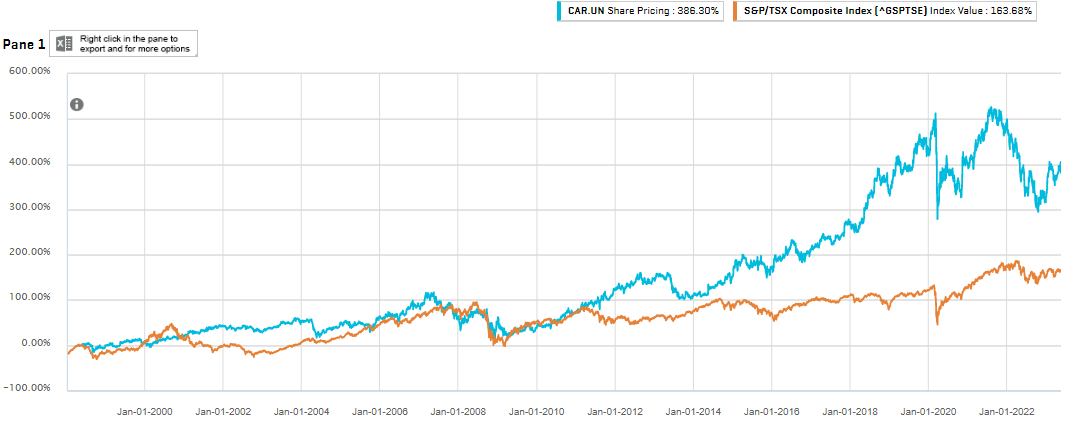

It’s a well run company that has outperformed the TSX by ~200% since 1998.

My interest in this company is first and foremost to have a vehicle to play a top-down macro bet. But as you will see below, there is also valuation upside in the stock itself. Let’s first dive into the macro though.

Demand for rent is strong.

Fertility

Demand for residential rentals in Canada is primarily a function of immigration. At 1.4, its fertility rate is way below replacement levels and it’s among the lowest in the world.

Immigration

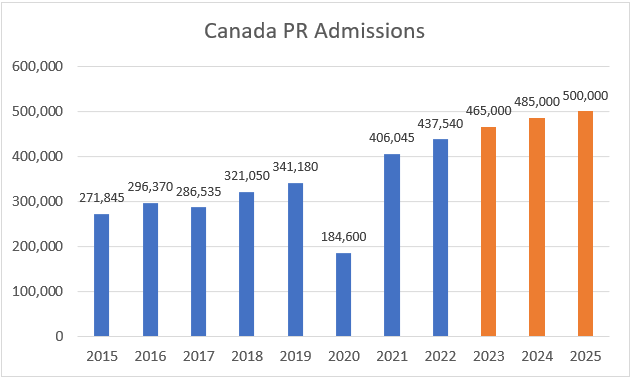

Canada has always been a country built on immigration. But they are currently taking this to another level and that is mostly flying under the radar of the global media machine. On November 1, 2022, the Canadian Government released the details of their 2023-2025 Immigration Levels Plan. They plan to ramp PR admissions to 500,000 annually by 2025.

This is a step change compared to prepandemic levels that were closer to 300,000 per year. And it’s surging Canada’s population growth already.

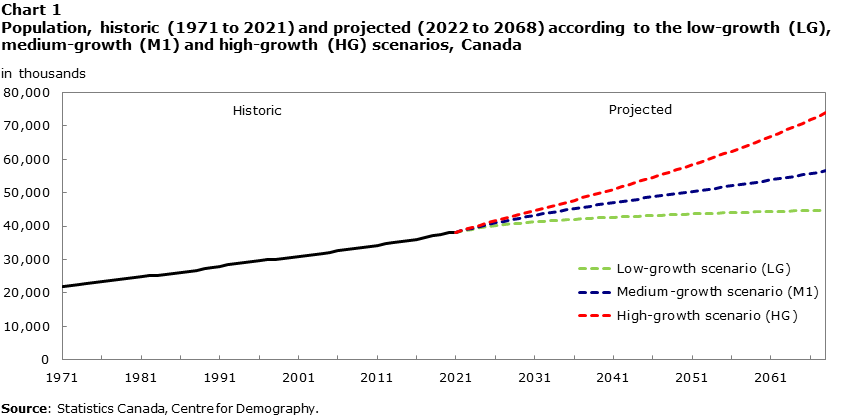

On August 22, 2022, Statistics Canada (StatCan) released their long term population projections. In 2021, Canada population was 38.2m. They expect this to grow to 57m by 2068 in their medium-growth (M1) scenario (+0.8% p.a.) and 74m in the high-growth (HG) scenario (1.4% p.a.). Comparing this to other countries is the best way to realize how profound such a growth rate is:

StatCan’s realtime population estimator is at 39.9m as of today, only weeks away from hitting 40m. Per the M1 scenario, this should not have happened before 2025. Per the HG scenario, it should not have happened before 2024. This means, Canada’s population is currently growing faster than the red line below.

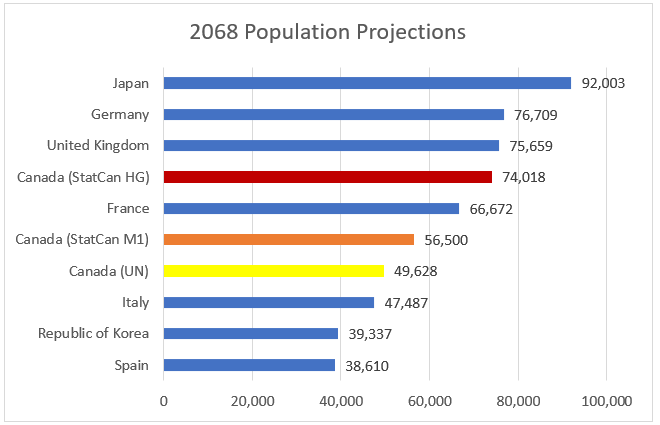

Over time, this growth differential vs. other countries will likely cause tectonic shifts in population sizes with presumably meaningful geopolitical implications.

Today, all of the countries below have larger populations than Canada. By 2068, Canada will likely surpass Spain, South Korea and Italy. And it will have a shot at reaching France, UK and even Germany!

You might rightfully object that important source countries for immigration, such as India for example, are dealing with demographic issues as well. Young people all over the world are effectively on procreation strike. But I would counter that Canada is small enough and attractive enough to receive applications for a very long time, even with a global baby bust in full swing towards mid-21st century. It offers supreme political stability and it is in an advantageous geographic location to remain attractive for immigration. I have moved to Canada five years ago and I am often amazed with how much gratitude newcomers approach their new life here. And they are welcomed with open arms by locals who know that these newcomers are needed as workers…and as exit liquidity for their homes.

All these immigrants will need housing. Will there be enough for them?

Supply for rent is not excessive.

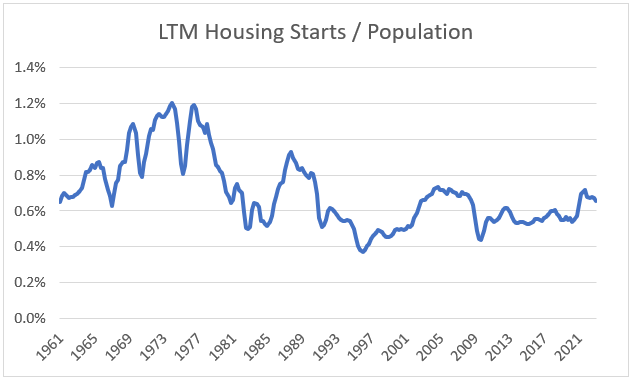

Over the past twelve months, construction has begun on 258k residential buildings, about 0.6% of Canada’s population, which is not elevated historically.

Compared to current population growth, it’s actually quite low. In fact, it’s the lowest it has been in the entire recorded history.

Some of that is potentially driven by a temporary surge in the denominator as Canada works through its post-pandemic immigration backlog. But some of it is likely driven by the unprecedented monetary tightening, which disincentivizes building and lays the groundwork for persistent shortages going forward.

Whatever the reason is, the result is what matters: there is not enough supply. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) is a federal crown corporation with the mandate to provide mortgage liquidity. They do so primarily by providing mortgage insurance. On June 23, 2022, they published a study titled Restoring affordability by 2030. Based on their (arguably subjective) definition of affordability, Canada will lack 3.5m housing units by 2030. That’s 20% of the entire current housing stock. And when they published this, they certainly did not expect Canada’s population to hit 40m a year later.

Good times to be a landlord ahead, don’t you think? Unless it’s all priced in.

So, is it?

There is upside in home prices and rents.

So far, I haven’t told you anything overly controversial. The figures I quoted may be new to you, but Canada’s housing crisis in general is well known. But it’s nevertheless not investable, right? Real home prices in Canada have more than tripled over the past 20 years. In nominal terms, they have even quintupled. In doing so, they have left various other countries far behind. Countries that themselves have had strong residential real estate returns. Priced to perfection, a bubble par excellence, isn’t it?

Is it really a bubble?

Home prices are now down 10% from their mid-2022 peak. It’s a significant correction from pre-hiking exuberance. But it doesn’t really qualify as a crash. And a bubble that never bursts is not a bubble. Its bursting is its defining feature.

Look, I get it. Canadian real estate is expensive and its pace is even more staggering that its actual level. But this requires an important qualifier: Lack of affordability is not a sufficient condition for prices to come down. We collectively negotiate prices for goods, services and assets (together “economic goods”) every single day through our actions and preferences.

And whether something is deemed affordable or not is relative. You might be used to get a haircut for $30 and you would be upset if they raised it to $60. But what if hairdressers had a different standing in our society, would be scarcer or people wanted haircuts more often? A haircut might then cost $100. And if the price dropped to $60, you’d be happy to get it cheaper than before.

The price of an economic good is a function of supply and demand and their price elasticities. It’s about relative and absolute scarcity. Whether the price of an economic good will rise or fall going forward is driven by its underlying scarcity trends. For real estate, scarcity has a monetary and a geographic dimension.

Scarcity in a monetary debasement regime

It will get a bit technical here. I encourage you to consciously read some of the key sentences twice. To make sure you can fully appreciate this section, please check out the article below:

In a nutshell: If a currency is not backed by a commodity, it is backed by the amount of economic goods that is priced in this currency. Prices will then remain stable as long as money supply grows in lockstep with the growth of these economic goods. Price appreciation of economic goods is therefore a function of how their scarcity changes vs the currency they are being quoted in.

To illustrate that with an example: If the housing stock remained unchanged, the Canadian population remained unchanged and their housing preferences remained unchanged, then home prices would hypothetically rise at the exact same rate as the money supply. If money supply growth exactly matches the growth in housing stock and the changes in demand from preferences and headcount, then home prices should hypothetically remain flat.

The truth is probably somewhere in the middle.

80% is the magic number

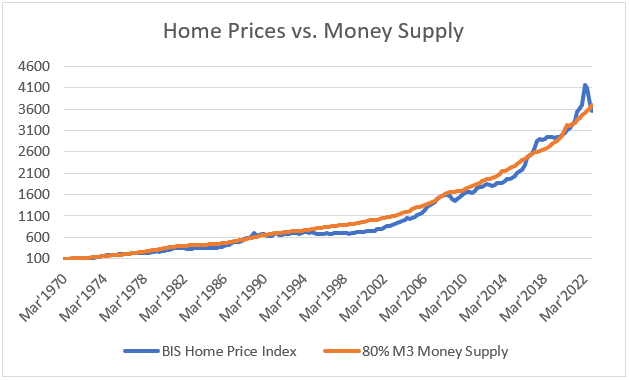

Since Canadian money supply has been outgrowing the housing stock, the latter has become scarcer in relative terms. I have illustrated that below. The magic number seems to be 80%, which means that home prices have grown at approximately 80% of the rate of money supply growth. When Tiff Macklem prints 1% more money, Canadian will see their home prices rise by 0.8%. At least on average for the past decades.

Since the correlation is strong, I believe we can reasonably assume that it will hold going forward.

The obvious follow-up: What do we expect from money supply going forward?

It has risen at 9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the past 50 years and the latest data point is 7%.

Yes, despite all the tightening and all the rate hiking over the past year, Canadian money supply is still 7% higher than one year ago. I believe it is reasonable to assume that it will continue to expand at a 7-9% rate. 80% of that is 6-7%. In my view, that’s the annual housing appreciation we can expect going forward. Over time, compounding like this will look like it’s going vertical.

Bubble Spotting

In my opinion, the most reliable way to spot a bubble is to look at step changes in growth rates. We humans don’t understand exponentials. So even a modest stable % CAGR will over time look like a bubble to us. But actual bubbles usually happen when growth rates (not prices) rise above their sustainable levels for an extended period of time. The visually most convincing evidence would be an upward bending log chart.

The chart below shows Canadian home prices on a log scale and compares it to the 5Y rolling CAGR. As you can see, this spiked a couple of times, most prominently in the late 1980s and mid 2000s. Both times were followed by substantial corrections and prolonged periods of sideway home prices. In the early 1990s, Canada had a proper debt crisis and the late 2000s GFC is well known.

Over the past 5 years, Canadian home prices have appreciated at just 4% CAGR. This is not overextended.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Fallacy Alarm to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.