GDP vs. GDI

The discrepancy between these two economic gauges is so extreme that it has become an economic signal. What is it telling us?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is our primary gauge to determine how the economy is doing. As the the name suggests, it attempts to measure our economy from a production perspective, i.e. what we achieve with our hands and brains collectively in a given period. It consists of the consumption of goods and services, private investment and public spending plus exports minus imports.

But it is not the only gauge we can use to meter the economy. There is also Gross Domestic Income (GDI), which attempts to measure our economy from an income perspective, i.e. what fruits we harvest from our economic activities. It consists of wages, corporate profits and mixed income from self-employment, financial assets and government transfer payments. It then adds taxes and deducts government subsidies.

In a steady state economy operating in a sustainable equilibrium, these measures should in principle be equivalent. After all, what we produce should be what we earn.

But that’s clean theory. Actual practice is muddy. There is always noise between those measures which can for example relate to timing differences or inconsistencies in data collection for example.

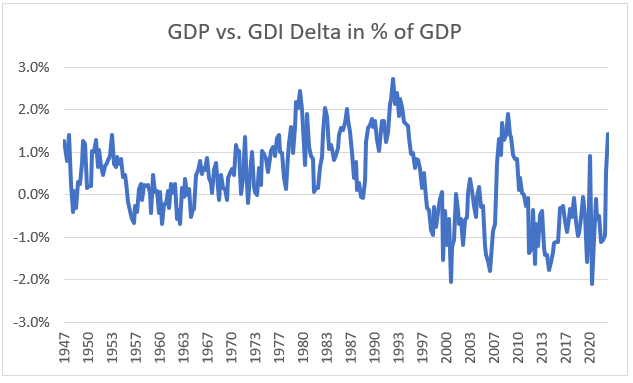

Sometimes, the noise becomes signal when discrepancies become sufficiently large that they can’t be assigned to imprecision in data collection anymore. In my opinion, we have reached such a moment in time.

While GDP keeps marching along and we keep waiting for the recession, real GDI remains below its 4Q21 peak as of 1Q23. Sure, there was a spike in 3Q22, but based on the chart below, someone could reasonably argue that we have in fact been in a recession for the entire past year.

The current annualized rate for GDP is >$300bn higher than GDI, which is the highest the delta ever.

In relative terms, the difference is not that pronounced, but it’s certainly a significant local extremum. Over the past 25 years, GDP has outpaced GDI to a similar extent only at the peak financial crisis in 2009.

Obviously, this delta can remain persistent and even expand further for quite some time as evidenced historically. But eventually, it will be mean reverting and perhaps overshoot in the other direction. After all, the delta has been negative most of the time of the past 25 years, suggesting that GDI usually outpaces GDP a little bit.

In this article, I will investigate where the delta might come from and what that might mean for the economy going forward.