Lilly and Novo obesity update

Lilly seems on track to take the obesity crown from Novo soon. However, both investment cases appear intact in spite of the recent consolidation.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not and should not be construed as investment advice. This is my investing journey and I simply share what I do and why I do that for educational and entertainment purposes.

In the article below, I took a look at Eli Lilly LLY 0.00%↑ and Novo Nordisk NVO 0.00%↑, both of which had been on a tear due to the obesity opportunity that arose from their legacy diabetes businesses.

15 months have passed since this article. Time for an update.

TLDR Summary

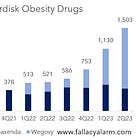

Obesity is moving into primary healthcare as an actual condition that deserves to be treated (rather than being one of the causes for various other conditions). This is highly disruptive for the entire healthcare industry and it is shaping a huge new subsegment: obesity drugs. Morgan Stanley expects this market to grow from basically nothing a few years ago to $105bn by 2030. Thus far, it seems that Lilly and Novo will have this value creation opportunity to themselves. Decades of research, developing and commercializing diabetes drugs have created huge moats that seem impenetrable.

It’s however a cutthroat race to get ahead and stay there. To maintain their market position and justify their valuations, both companies need to reiterate their compounds regularly to move the efficacy/tolerability frontier forward.

At the moment, Lilly seems to have done the better job. Their tirzepatide handily beats Novo’s semaglutide in terms of efficacy. And while Novo’s latest trial result on an updated formulation indicated efficacy improvements, it also raised tolerability issues, the Achilles heel of obesity drugs.

While Novo has sold off more in recent months, both stocks have actually consolidated. The same is true for a few other players in this space. Much of the hype has worn off, valuations have somewhat normalized. Investors are playing other themes right now. This might provide for a dip buying opportunity.

Contextualizing the opportunity

Obesity is currently in the process of moving into primary care as a standalone condition that deserves to be treated. Before, it was merely considered a cause of actual health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, coronary heart disease, cancer or NASH (fat liver). This transition will likely create an obesity drugs market worth hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Morgan Stanley projects the global obesity drug market to reach $105bn by 2030. A year earlier, they only thought it would reach $77bn by then.

It’s not a coincidence that this market is emerging from the diabetes segment. Insulin is a hormone that regulates the sugar levels in our blood and cells. When we eat, sugar accumulates in our blood. The pancreas then releases insulin to inform body cells that they should open their doors to take in that sugar to consume or store it. Its opponent is glucagon which increases blood sugar by breaking down muscle and fat tissues.

With diabetes, either the body’s ability to produce insulin is compromised (Type 1) or the cells’ willingness to respond to it can be reduced (Type 2). Most people with Diabetes suffer from Type 2. As a result, the sugar remains in the blood and will start causing damage. Traditionally, diabetes patients would then take additional insulin as medication to force the sugar from the blood into the cells.

GLP-1 is a hormone that is actually naturally occurring in the body. It was first identified in the 1980s and over the past years and decades it has demonstrated various noteworthy functions which include

stimulating insulin release,

preventing glucagon release,

delaying gastric emptying, i.e. the rate at which nutrients are absorbed into bloodstream and thereby

suppressing appetite.

The name glucagon-like peptide 1 is actually quite misleading because its function is actually the opposite of what glucagon does. The reason for its name is that it shares chemical similarities with glucagon. So, when scientists found it in the 1980s, they named it after glucagon, at that time not knowing what its function is.