Ten Trillion Dollars

Why QE will be back soon in XXL format and how its return will likely be forced into existence.

Before we dive in: Fallacy Alarm has now surpassed 2,000 subscribers. Thank you so much everyone for your support. It is very motivating for me to keep going and live up to your expectations. As a result I am actually tackling a lot of the questions I have been asking myself with much more rigor than when I only wrote to myself.

To celebrate this milestone, I am offering 14-day free trials via the link below (to be redeemed by March 15). This will give you access to the entire article archive of ~70 articles, incl. the podcast episodes and the Excel workbooks I have created to perform the calcs for some of my articles. The free trial will also enable you to read the 2nd half of this article for free. :)

The goal of this article is to answer the following three questions:

Why will the Fed likely restart Quantitative Easing (QE) soon?

How big will that QE program be?

How will it come into existence?

This article was inspired by a discussion I had with Raoul Pal. Thank you for your support and your insights, Raoul!

My macro framework is built on the realization that we’re in a demographic trap that makes it challenging for us to keep up growth of aggregate economic output at levels that we are used to and that our economy requires to function. As a result we have propped up the economy again and again by taking bigger and bigger sips from the debt bottle, effectively pulling future demand to today, making future growth even more difficult to achieve.

We are now hitting the limits of this mechanism. With the enormous debt supply via endless deficits, interest rates want up obviously (which in itself increases supply further). To avoid that, central banks have been funding the debt binge in the US and globally with freshly printed money based on nothing. Over the past 15y, they have bought large amounts of government debt and other financial assets, aka they performed QE.

The result of this process is recurring monetary debasement, which bails out investors and debtors at the expense of savers and creditors by suppressing (real) interest rates. It causes inflation primarily in asset prices and against the narratives you are hearing out there it does not necessarily cause consumer inflation. It is in fact very deflationary in the long run because it removes demand from the future.

The three articles below summarize my framework fairly comprehensively if you’d like to study this in more detail. I have spent A LOT of time thinking about this.

The Demographic Deflation Bomb is ticking

Here is why I am so adamant that (real) interest rates will fall

As laid out in these articles, I believe that 2022/23 is not a trend reversal. Instead it is an outlier in an ongoing trend, a massive bear trap. I am convinced that we will soon get QE again. It will be the biggest QE program the world has ever seen. And it will have profound implications for asset prices.

What we can

It all starts with economic growth. Per its literal definition, GDP is what we collectively produce. But it also refers to what we collectively spend.

Debt can be raised for productive purposes or for unproductive purposes. You can use it to buy an investment property or a nice car for example. If you do the former, your ability to spend will grow because your income grows. If you do the latter, your ability to spend will decrease. You have to service your loan on an unproductive depreciating asset. If you buy a car on credit today, you won’t buy it with your savings tomorrow. Raising debt for unproductive purposes pulls future demand to today and therefore it reduces growth prospects.

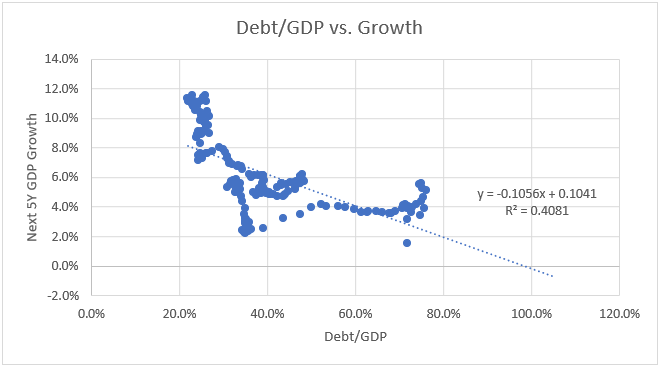

It therefore does not surprise that the growth rates in the US economy have come down over time as the debt burden increased. The chart below shows the federal debt held by the public (i.e. with intragovernmental debt cancelled out) as a % of GDP vs. the subsequent 5Y average GDP growth.

Nominal GDP advanced at about 8-10% in the 70s/80s with 20-30% Debt/GDP. In the 90s, the economic growth was 5-6% with 50% Debt/GDP. In the 2010s, we got 3-4% with 70%.

Debt/GDP is now 95%. If the regression analysis in the chart below is any good, we can *hope* to get 1-2% growth at most. *Nominal* growth that is by the way. So, it’s pretty much stagnation.

But economic growth is not just a function of indebtedness. It is also a function of population growth, particularly growth of the productive portion thereof. As you can see below, the growth of the 20-64y age group has historically explained nominal GDP growth in the US very well:

Per the United Nations, the 20-64y age group in the US is expected to grow by 0.2% annually for the next years and decades, which would translate to just under 2% nominal GDP growth per the regression equation above and it corroborates the estimate based on the debt burden very well.

By and large, I think we can expect annual GDP to grow by $5tn over the next 10y. That would be 1.8% nominal annual growth.

What we want

The US federal budget deficit is projected by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to amount to ~$20tn for the coming decade (technically 24-33 in the table below, but I’m a butcher, not a surgeon anyway).

This results into a ~6% annual deficit, which will be rising over time…

…which will bring federal debt to unprecedented levels.

Even if these figures appear insane, taking the CBO at face value is actually conservative at best and naïve at worst in my opinion. Call me a cynic, but I am convinced they will always find new emergency situations to decide on a new spending package. The budget assumes for example that the IRA will cumulatively reduce the deficit by $200bn, when it is way more likely that it will actually increase the deficit by $1tn over 10y. I have written about that in the article below:

I think the cumulative deficit could easily be $25tn over the next 10y. But for the purpose of this analysis, I will nevertheless give them the benefit of the doubt and work with their projections. It will be sufficient to make my point.

And the gap in between

If we perpetually ‘want’ more than we ‘can’, we have a problem obviously. There are a couple of ways how those two can be reconciled.

First of all, we could simply ‘want’ less. We could reduce spending so that the deficit matches economic growth, which should be a stable economic equilibrium. It is certainly possible. The values of our society can change. And I am not here to judge and tell you what *should* happen. This is not a political blog. I am here to figure out what *will* likely happen. The likelihood that this will happen is negligibly small based on my reading of the political arena, which is why I comfortably dismiss this scenario. We’re used to 6% deficit spending and the perks that come with it. Reducing that to a more sustainable level of 2% (after accounting for interest expenses), means improving the federal budget by $1tn annually. Raising taxes to that extent would cripple the economy and cutting spending to that extent would send the mob into the streets.

So, if we ‘want’ more than we ‘can’, then somebody has to pick up the tab and give the $$$ to us.

$20tn new debt vs. $5tn new GDP. There is only one guy who can do it.

The chart below shows how Debt/GDP has evolved over time with and without the portion that is funded by the Printer.

As you can see, the more the debt burden climbed, the more the Fed stepped in. As of now, they own $6tn or 25% of the Treasury debt.

What is the most likely scenario where this is headed?

If GDP grows by $5tn and debt grows by $20tn, then Debt/GDP will grow to ~140% by 2032. I have considered two scenarios below:

The Fed could keep their share in Treasury debt constant, i.e. new debt will be funded by investors and the Fed with portions corresponding to the current allocation. This means that investors would be willing (and able!) to fund the Treasury deficit with a sustainable interest rate at even higher Debt/GDP levels than today. I consider this a quite optimistic scenario.

Investors could fund future debt only to the extent that a stable Debt/GDP ratio will be maintained. The remainder will be funded by the Fed. This basically assumes that US Debt/GDP is maxed out at current levels from a free market perspective. So, higher leverage must be printer-financed. I consider this a rather pessimistic scenario.

As illustrated in the chart above, this means we will require $5tn to $15tn QE over the next 10y. Ten Trillion Dollars at the midpoint.

$500bn to $1.5tn annually on average. It is important to visualize the significance of this. The Fed’s balance sheet grew by $3.5tn in total between 2008 and 2018. And it grew by another $4tn since the arrival of the plague. So, we are talking here about a QE program that will likely be 2x bigger than the aftermath of the GFC and it will likely be bigger than everything the Fed has done between 2008 and 2021 combined.

I can hear you object. $21tn of federal debt held by the Fed at the high end of my range. Is that not insane? That would be ~70% of GDP and more than half of the entire debt outstanding. Unprecedented and impossible!

I don’t know whether it is impossible, but it is not unprecedented.

The Japanese are leading the West by one to two decades in many things, demographics most importantly. It explains why they had their dotcom crash 10y earlier, I have written about that in the article below.

Check out the chart below, which shows their Debt/GDP over time with and without what is BoJ funded.

Debt/GDP now stands at 230%. The investor-funded Debt/GDP is at 131%. The BoJ owns 44% of the entire government debt. And most importantly, the BoJ has been the net buyer of most new debt for the last 10y. The investor funded portion of Japanese government debt has come down a lot as a % of GDP over the past 15y. There was a global reversal of many trends around 2010 will probably warrant an entire article on its own at some point.

And how will it happen?

Obviously Jerome Powell will not just wake up one day, clap his hands and be like: ‘Today is a great day to restart the Printer!’

It’s way too unpopular due to inflation fears and our collective feelings towards what is just. QE has a bad image. It increases inequality and reduces social mobility because it jacks up asset prices and devalues debt (both of which helps the rich more than the poor).

So, as usual markets will have to force him. In my opinion, this will unfold via what I call The Double Flywheel for Treasury Yields. It is happening already and it consists of two components, the Supply Wheel and the Demand Wheel.

Supply Wheel

There are principally two approaches how to think about markets in general, and the treasury market in particular. You can either assume an efficient market that properly prices in future expectations (fundamental approach). Or you can assume that it is simply subject to supply and demand forces (technical approach).

From a fundamental perspective, I would like to introduce you to Tom McClellan, who is a market strategist. His hypothesis is that the 2Y Treasury Yield forecasts where the FFR is headed. If it is above the FFR, it signals to the Fed to hike. If it is below the FFR, it signals to the Fed to cut.

The underlying rationale relates to this previous article, when I mentioned that functioning financial markets require a positive term risk premium. So, in a neutral equilibrium an overnight rate like the FFR should be close to and just under the 2Y yield. By over/undershooting the FFR , the 2Y is sniffing out where this neutral level is.

This indicator was very powerful for me in late 2018 / early 2019 when it helped me to BTFD. But more and more I feel like that this time might be somewhat different.

The more the Treasury levers up, the higher the interest rates they will have to offer to find enough demand for the Treasury securities. This process is self-reinforcing because these rising interest rates will increase the deficit, which will increase supply of Treasury securities even more. I believe we are heading towards an inflection point (if we haven’t passed it already) where the supply demand imbalances are so severe that markets lose their ability to carry out proper price discovery. Instead of signaling their anticipation of an inevitable QE program via falling yields, markets are actually screaming for QE with rising yields. When prices are utterly unsustainable, but markets go there anyway, then we’re in pain trade territory, not in price discovery territory.

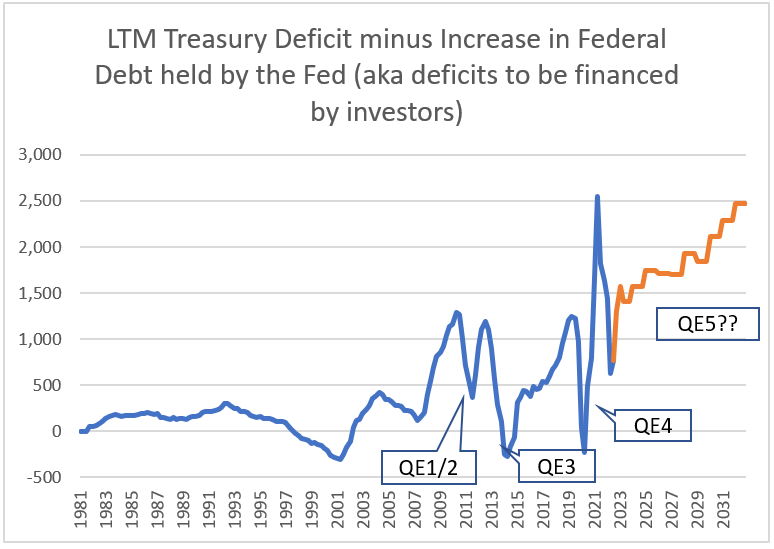

Check out the chart below for example. It shows the LTM Treasury deficit minus the increase in federal debt held by the Fed. This is basically the amount of debt that Janet Yellen needs to sell to investors without the help from the Printer. Blue is historical, orange is projected based on CBO budget and assuming the Fed won’t buy any of it.

I find it highly doubtful that there will be enough buyers for this wave of debt without a QE program, whether it is initiated in the US or abroad. Like a vacuum cleaner, the Treasury will suck up all investor money available and to do so they will have to offer higher and higher interest rates. And that sets a vicious cycle in motion. At 4% yields, their colossal $24tn debt balance will eventually demand $1tn in interest payments.

Demand Wheel

Demand for a currency can come from two sources:

Trade balance: Strong international demand for domestic production increases demand for the currency to pay for it.

Capital balance: Strong international demand for domestic investment opportunities increases demand for the currency to pay for it.

Let’s assume there are only two countries, X and Y. X has a chronic trade surplus with Y which causes ongoing demand for their currency to buy their products and services. You would generally expect X’s currency to appreciate vs. Y over time. Germany, Japan and China were good examples for X for many years. And the US obviously for Y.

However, there can be a stable equilibrium in the X/Y FX rate as long as X reinvests proceeds back in country Y. This can happen in various ways. Perhaps X’s citizens are interested in investing into Y’s stock market. Or X’s corporations are interested in building factories in Y or loaning money to Y’s citizens to buy their products. Or, ultimately, X’s government directly buys Y’s government bonds to massage the FX rate on purpose. As long as there is such an equilibrium, this process can continue forever. Contrary to what many seem to believe, a chronic trade/capital account surplus/deficit can in fact persist forever.

But what if there is not an equilibrium? What if interest in investing in Y is not enough to fund their trade deficit (case 1)? Or what if interest in X products and services is not enough to fund capital flight (case 2)?

Then X/Y FX rate will adjust up and down to find an equilibrium. In case 1, Y’s currency will depreciate, which will decrease their imports (their currency buys less) and bring the balance of payments back into equilibrium. In case 2, Y’s currency will appreciate so that it will be more difficult for money from X to invest in Y. Also, it will make X’s products more competitive, thereby increasing their trade surplus and helping fund X’s desire to invest in Y.

But what if this FX rate is seemingly close to infinity? Welcome to the USA in 2022 and potentially 2023. It seems to be a perpetual cycle of rising interest rates, followed by further capital inflows, USD appreciation, making it more challenging for foreign investors to invest in Treasuries, raising interest rates further and the death spiral continues.

It is the severe mismatch between fiscal and monetary policy in the US that causes this death spiral. I have written about that in the article below as a potential scenario. It was not my base case at that time, but it appears we’re headed into that direction.

One way or another this mismatch has to be resolved eventually. Debt supply must directionally be aligned with money supply. Otherwise interest rates will spiral out of control.

What we have been seeing over the past year, namely rising Treasury yields and a strengthening USD, means that markets are screaming for more $$$. They are screaming for QE. I believe this process will continue until the Fed reacts by opening the flood gates once the impacts of nosebleed interest rates will become visible. The most interesting question about the coming months and years is not whether we will get QE. It is only a question of when and and how it will unfold. I can imagine that it will come with some form of temporary pain, a liquidity scare in financial markets as they force Jay’s hand.

Considering what the endgame will most obviously be and also considering the extremely bearish overall positioning, I do not think it makes sense to bet on or hedge this temporary pain. It does not make sense to me to hedge a 20% downside scenario at the expense of potentially not participating in the subsequent 200% upside.

In 2019, the Fed cut rates and opened the gates simply driven by dropping inflation expectations while the market was in the middle of a bull. My base case is that 2023 will rhyme with that and we will see a strong upward impulse in equity markets this year that may or may not be accompanied by a comparable impulse in bonds.

Sincerely,

Your Fallacy Alarm

Care to share your best guess on how high the FFR goes?

I agree with you that QE5 is an inevitability at some point in the future, but was thinking it would come as a result of economic weakness, rather than a problem in the financial markets, although the turmoil and panic in UK Gilts last year is clearly a sign that this can happen in large, liquid sovreign debt markets. Have we become completely dependent on our Central Banks, not as lenders of last resort, but bond buyers of last resort in an ever increasing debt spiral that strenghtens that dependence as it piles up whilst becoming increasingly difficult to grow our way out of? How can we avoid this spiralling out of control?