Where is Tesla's demand cliff?

There is more to it than just tracking wait times and price increases.

The health of the production constraint thesis

When I was young, there was a company named Wiesmann near my hometown that specialized in designing and manufacturing stunning retro style sports cars with a modern touch:

The company was founded in 1988 and had a loyal fanbase for whom they hand-built 180 vehicles per year. Business went well and Wiesmann even planned to export to the US by 2010. But then the company was hit by challenges to keep production and distribution costs in check and they had to file for bankruptcy in 2013. My interpretation: At some point, everyone who wanted to own a Wiesmann and could afford it at a price sustainable for Wiesmann was already in possession of one and demand fell off a cliff. The company’s international expansion plans came too late and they did not sufficiently work the costs down before.

There are tons of examples like this, not just in the automotive industry, where phenomenal growth stories imploded because the eventual market size was totally overestimated at the given production costs.

The notion of Tesla being production constrained is extremely important to the investment case. Not only does it make them less vulnerable during a recession, it also provides comfort that they can achieve their lofty production targets. It is therefore very important to continuously monitor whether it is still true.

To understand whether there is a demand cliff for Tesla requires understanding the difference between replacement and conversion revenues, their race between production growth and cost declines, the fact that they are not advertising as well as indirect demand clues such as the fact they are not introducing new products in 2022 and how their price increases and wait times track. Let’s dig into these aspects:

Replacement vs. Conversion Revenues

A very important aspect to assess Tesla’s demand curve is that currently most of their revenues happen to first time buyers, which I call Conversion Revenues, because a BMW owner for instance is being converted to a Tesla owner. This is in contrast to most other brands. The global automotive market is pretty much saturated with stable market shares, so basically all unit sales are what I call Replacement Revenues. Most of the time a BMW is sold, it replaces an old BMW. This means one cannot compare 2m Tesla sales with 2m BMW or Ford sales. For the time Tesla has not yet achieved their sustainable market share (in terms of installed fleet, not annual unit sales), i.e. as long as not everyone who wants a Tesla has one, they will be able to command a higher share in annual unit sales then warranted by the sustainable installed fleet level. This adds to the growth curve. This is also true for EVs in general by the way which will cause a temporary growth bump in the automotive industry in the peak transition phase once EV production is large enough before the market will settle for lower volumes.

I will illustrate this with an example. There are approximately 1.5bn cars in the world and 75m unit sales per year, indicating a 20y average replacement cycle. Let’s look at two companies. The first one is legacy manufacturer L, which commands a 10% market share in annual unit sales and has done so for the longest time making their share in the global installed fleet also close to 10%. They have a solid brand, owners are happy and it is likely they will continue to defend this market share for the foreseeable future. The second company is challenger C. C just entered the market and has a negligible share in annual unit sales and global installed fleet. However, they have a compelling product with a loyal fanbase. They are also technological frontrunners and are showing strong signs of superior ability to scale.

Let’s say both companies have equally compelling brands/products and the ability to produce at scale. L will continue to sell 1.5bn / 20y * 10% = 7.5m vehicles per year and is entirely demand constrained along the way (therefore tons of advertising). These are mostly Replacement Revenues. L is dependent on each of the 1.5bn * 10% = 150m owners to replace a vehicle once every 20y and choose the same brand again.

The demand curve for the C is however is totally different since they are not dependent on Replacement Revenues. Instead C can tap into the void of 150m potential owners who do not own them yet, but eventually would like to. Assuming it will take one entire global replacement cycle of 20y to tap fulfill the customer demand, C has the potential to sell 150m / 20y = 7.5m vehicles per year as true Conversion Revenues. If they do so, they will be able to generate 71m (or 3.6m per year) in Replacement Revenues along the way.

So, while both companies will eventually command the same market share and have the same number of customers, L will have on average 7.5m unit sales per year over the coming 20y and C will have on average 11.1m unit sales:

If you have not followed the math above in great detail, here is the punch line: If you believe that Volkswagen and Tesla will have equal market shares eventually and the transition period to that end stage will take 20y, then Tesla will be able to sell almost 50% more vehicles over the entire 20y span than Volkswagen! I am emphasizing this so much because I don’t think many people are aware of this aspect since everybody looks at unit sales market share as opposed to global installed fleet market share.

Race of unit growth and affordability

In order to achieve their lofty long term revenue targets, it will be a tough race for Tesla to get production costs down with unit growth because the more they want to sell, the more they need to tap into low cost segments. Something Wiesmann did not understand, but Elon understands it very well. In contrast to many other companies, Tesla operates based on the principle that every product or business activity has to be self-funded. There are no loss leaders in the Tesla system. I have written about it here:

And Drew Baglino talks about it here as well at around the 50min mark:

And lastly, you can find more detail on how advanced Tesla’s long term scale planning is compared to their competition here:

So, a good part of the answer to whether can sell 10m or 20m vehicles is whether they can decrease costs with rising production. They have shown good progress over the past years and laid out the roadmap to 2030 transparently in very much detail during the 2020 Battery Day. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend checking that out. And don’t just read the slide, listen to the replay as well.

In case of any hick-ups along the way when production unit growth outpaces the cost decrease required, they have a built in buffer due to their fantastic margins due to which they can lower prices to get the volume into the market until production efficiency catches up.

No Advertising

One of the favorite activities of Tesla bears on social media is to dig into Tesla’s EV market share in certain end markets and conclude that other companies are eating their lunch. This whole activity always felt pointless to me. Let’s leave aside for a moment that total vehicle sales matter (as opposed to EV only) and global sales matter (Tesla can always ship production to new countries if necessary). These points are widely advertised by Tesla bulls on social media.

The key counter argument to me is that Tesla does not spend a single $ on advertising their products. How can this company be any close to having demand constraints? Compare that to the other manufacturers who rub their latest vehicles into our faces everywhere from Online Ads, to TV ads, to banners in the public space to lottery prizes and sports sponsoring. I am not a car person, but I can pretty much tell you the entire pick-up truck line-up available in North America. I even feel like buying one sometimes although I hate pick-up trucks! Can you believe it? That is the power of advertising. And Tesla could easily pull that lever if they had to.

Commercial applications

But even if consumer demand vanishes in a recession, Tesla can use the cost of ownership argument to replace tons of commercial fleets: taxis, post, police...anyone who operates a large fleet will naturally be a Tesla buyer. Today, a Model Y is a premium product. But it will become a Camry in a couple of years. A workhorse printed by their factories in millions a year. I do not think many people understand how omnipresent the Model Y will be in our lives in just a few years.

No new products in 2022

For me, the strongest indicator that the production constraint thesis is as strong as ever was when Elon said in the 4Q21 earnings call that they postpone all new products this year to ramp existing products as fast as possible.

The fundamental focus of Tesla this year is scaling output. So both last year and this year, if we were to introduce new vehicles, our total vehicle output would decrease. This is a very important point that I think people do not -- a lot of people do not understand. So last year, we spent a lot of engineering and management resources solving supply chain issues, rewriting code, changing our chips, reducing the number of chips we need, with chip drama central.

And there were not -- that was not the only supply chain issue, so -- just hundreds of things. And as a result, we were able to grow almost 90% while at least almost every other manufacturer contracted last year. So that's a good result. But if we had introduced, say, a new car last year, we would -- our total vehicle output would have been the same because of the constraints -- the chips constraints, particularly.

So if we'd actually introduced an additional product, that would then require a bunch of attention and resources on that increased complexity of the additional product, resulting in fewer vehicles actually being delivered. And the same is true of this year. So we will not be introducing new vehicle models this year. It would not make any sense because we'll still be parts constrained.

Elon Musk, 4Q21 earnings call

Many people did not acknowledge that much or even read it as negative. But it was hyper bullish to me. At that time I was already getting very nervous about the prospects of a global economic slowdown, so I wanted to own investments that had a huge growth runway with a large demand cushion to be protected from a cyclical demand contraction.

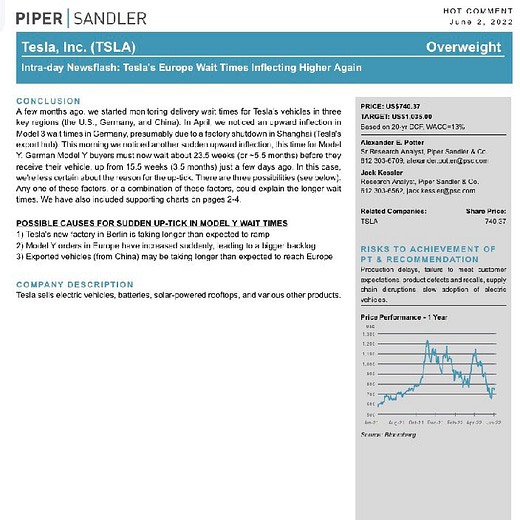

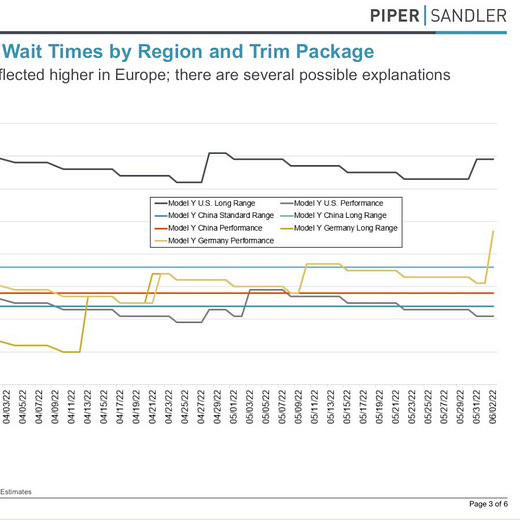

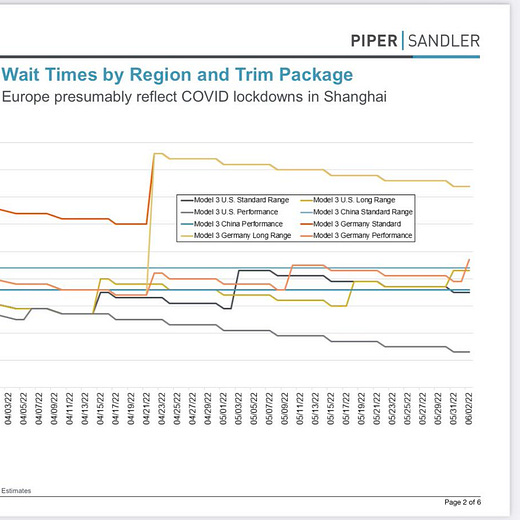

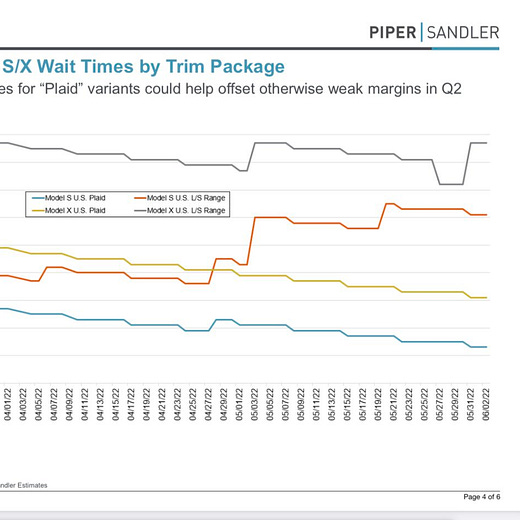

This comment alongside various price increases and information on increasing wait times proved to me demand for existing products is off the charts. Twitter is a great source to keep up with price increases and wait times. Here are just a few examples I have seen recently:

The Bottom Line

I will continue to challenge myself regarding the assumption that the demand curve is indeed irrelevant to the Tesla story for the time being. But for now, I am very content with the information I have at hand. Let me know what you think! Also, please share me with friends and colleagues, if you enjoy the content. The bigger this blog, the more time I will be able to spend on writing more.

Sincerely,

Your occasional Fallacy Alarm

More information about Tesla profits in next decade n cashflows with their new product development like BoTS , Tesla Energy ,