The Great Pandemic Era Option Bubble

It pumped stocks. It crashed stocks. And now it is history.

This article explains the last 3y from an angle you might not have heard before and the implications are profound in my opinion. While it is quite technical to follow, I encourage you to work your way through even if option trading might not be your forte or particular area of interest. I will try to convey my message as clear and digestible as possible. Happy to discuss any questions! Feedback will help me to clarify what is unclear in future articles.

“You did what you did to me,

now, it's history I see.

Here's my comeback on the road again.”

Alphaville, Big in Japan

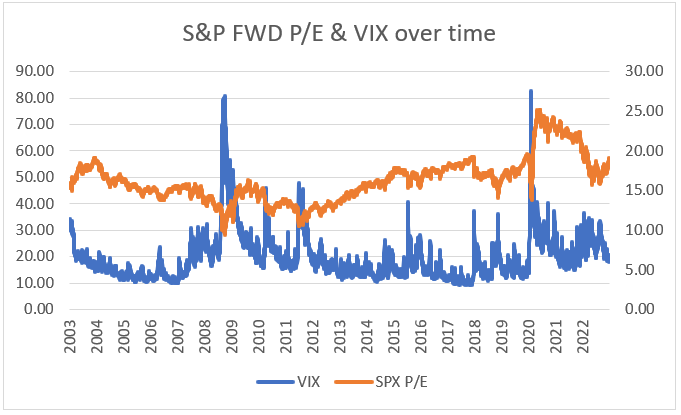

Let’s jump right in with the key observation that led me to writing about this: The regression analysis below compares the S&P Forward P/E Ratio to the VIX. And it does so by looking at two distinct periods: 2003-Jan’20 and Feb’20-today.

It is visually obvious that there is a clear negative relationship between the S&P P/E and VIX and that this relationship underwent a profound change after January 2020.

The chart raises a few questions that I will attempt to answer in this article:

Why is the relationship negative?

What changed after January 2020?

What does that mean going forward?

1. Why is the relationship negative?

The CBOE Volatility Index, in short VIX, is the most popular measure for expected stock market volatility. It is calculated as the expected annualized S&P volatility for the coming 30 days based on S&P option prices. The chart below shows how it moved over time vs. the S&P Forward P/E Ratio:

As you can see, when the P/E tanks, the VIX moves up and vice versa. The reason for this can be found in the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) which postulates that investors are pricing assets based on systematic risk, which is defined as volatility. They are generally risk averse, i.e. volatility averse. That is why they require higher returns if they have to bear higher volatility. If they deem future volatility for the S&P higher today vs. yesterday, they will price the S&P (and its earnings) lower to reflect that higher rate of return. As a consequence, the multiples goes down.

In the past - depending on the level of the VIX - the multiple typically contracted at a rate of ~0.1-0.2x for every 1 unit increase in the VIX. The lower the VIX, the more impact it had on the S&P P/E.

After January 2020, this relationship fell apart. You can see it visually in the chart above, but you can also see it in the R-Square formula in the first chart, which dropped from 0.32 to 0.12. Pretty much the difference between statistically significant to statistically not significant.

2. What changed after January 2020?

When policymakers crashed the global economy in 2020, they created a lot of economic uncertainty that lasted for at least a year, if not longer. Global scale lockdowns had never happened before and many people (incl. me) worried that it would have devastating consequences.

At the same time though, they flooded financial markets with liquidity and created the loosest financial conditions ever. They provided fiscal stimulus via direct payments to consumers and they bailed out companies by directly underwriting their credit risk. As a result, interest rates and credit spreads tanked. Yet, uncertainty with respect to the future of the real economy persisted. All of this created a rare instance of a powerful bull market with persistent high implied volatility. The 2020/21 bull market ran on fear. People never really trusted it because everything was just counterintuitive.

These fears were unwarranted most of the time. As you can see in the chart below, the volatility priced into the option chain was consistently lower than the actual realized volatility for that period.

As this unique economic and financial set-up unfolded, option markets went completely bonkers. Per the OCC, the world's largest equity derivatives clearing organization, annual cleared contract volume in 2021 was 100% higher than 2019.

And these are just contracts. The S&P as a representation of the entire stock market was about 30-50% higher in 2021 compared to 2019, which means that the $ options volume had probably grown by 130-150% over 2y.

We can only speculate what caused this. The digitization boost that came with the lockdowns certainly played a role. Millions of people more or less locked down at home had more time and less supervision. And providers like Robinhood and Interactive Brokers provided easy access. And the market itself was very enticing given how violent the upmove was.

But following this avenue of thinking is dangerous because it quickly brings up a chicken and egg question: Did the bull market cause the option bonanza or did the option bonanza cause the bull market?

To understand this, we first need to understand how options impact stock prices.

Consider a hypothetical stock and its derivatives to be in complete equilibrium. Everyone owns as much of stock, calls and puts they want to and at the price they like it. No trades happen.

Now comes a bull B who wants exposure. He can either buy the stock, buy a call or sell a put. Therefore, he must find someone who wants to sell the stock, sell the call or buy the put. Since everyone is happy and markets are in equilibrium, nobody wants to do that at current price and implied volatility (IV) levels. IV equals exactly the volatility that market participants expect in the stock going forward.

Let’s say B goes down the route for the call. He must offer a price for the call above current option prices. A pure arbitrageur counterparty C (C as in Citadel perhaps;)) will then show up and fill him because someone offers a higher IV than the market generally ascribes to the stock.

C can then try to hedge somewhere in the option chain, but every move in there will be zerosum. Any other call or put trade would create another imbalance. Ultimately, any overhang regarding buying and selling in the option chain must be settled in the stock to bring both, stock and option chain, back into equilibrium. Therefore, C will buy the stock and becomes delta-neutral from his short call. Since the stock price was in equilibrium, he will only be able to do so by bidding the stock above the current price of the stock, which will move the stock up.

After B’s market entry has been digested, the price of the stock and the IV in the option chain are both up.

If B sells a put instead, he will only be able to do so below current IV since the market is equilibrium. C will buy the put from him and buy the stock to become delta-neutral.

If B buys the stock, the stock will rise and the option chain won’t be bothered (at least not directly if market participants’ views on volatility won’t change).

The same logic also applies when a bear enters a position by selling the stock, selling a call or buying a put.

In summary:

Then we need to understand Options and Leverage.

Call options are effectively leveraged bets on the stock. With any given size of investment, you can control more shares than you could by buying outright shares instead. You pay interest for that in the form of time decay. If nothing happens to the stock, the call option will gradually lose value.

As illustrated above, when a market participant buys a call, eventually there will be someone who will buy shares once all effects from buying the call have rippled through the orderbook of stock and option chain. This ‘someone’ does not necessarily need to be a market maker, but they usually are the counterparts to most option trades. So, when you buy a call, you effectively buy stock on credit. The market maker is your lending bank, your stock custodian and theta is the interest you pay them.

In 2020 and 2021, the market has been pumped up by a massive call option open interest. Bubbles require leverage to come into existence. And this leverage happened in the option chain.

This brings us to the most important question I am trying to answer today:

What does that mean going forward?

If we had a bubble due to leverage hidden in option contracts, has this bubble sufficiently deflated and we’re safe? In my opinion, the answer is a resounding Yes.

And here is why.

Let’s assume we were fine on January 31, 2020. I know perceptions on this differ wildly, but in my mind we had just shaken off 2019 recession fears and markets were in the process of popping. They were initially unfazed by the disturbing news out of China and later Italy and the crash did not start until it became very clear that policy decisions would be devastating.

If we want to isolate the effect of the step change in the P/E to VIX relationship after January 2020, all we have to do is taking the January 31, 2020 P/E ratio and then extrapolate it into the future based on the VIX changes and regression equation. The result is a hypothetical path for the S&P assuming that the P/E to VIX relationship had remained the same that it was before. Plotting that in a chart looks like this:

As you can see, the actual S&P recovered much quicker than the hypothetical S&P. I don’t have proof, but I find it absolutely plausible that this delta was driven by call option leverage. And I also believe that the persistently higher IV in a second step attracted flows into short puts, which is a leverage employing strategy as well. Writing puts is an income strategy, which was very attractive considering elevated IV, particularly considering that interest rates had collapsed which made money chasing alternative income generation assets.

The difference between the actual S&P and the hypothetical S&P in the chart above is what I call the Great Pandemic Era Option Bubble. And as you can see, the gap closed by mid-2022. Closing this gap was in my view significantly driven by deleveraging in the option chain.

Interestingly that is exactly what I predicted almost to the day one year ago!

I got that directionally right. The only thing I completely underestimated was the magnitude of this and how long it took to be digested.

Last fall, we mildly undershot the P/E-to-VIX model to the downside for a couple of months, which is quite typical when a bubble deflates. But I am optimistic that we can leave this bubble behind. I do not see much downside anymore in the option chain that needs to be digested.

But Fallacy, 0DTE!

0DTE? For those of you who do not follow this stuff with my degree of obsession: There is a new trend in option markets, which is gambling with so called 0DTE options, i.e. options with zero days to expiry.

Their share in total option trading volume has surged from ~10% in 2019 to >40% today:

This makes many people nervous. This guy even compares it to the portfolio insurance fall-out that caused the 1987 crash.

I might regret this, but I am going to say it: 0DTE is a nothing burger.

Here is why:

First of all it is important to understand why this boom in 0DTE happened in the first place.

Again, buying a call option is like buying stock on margin. This means the call option buyer needs to pay interest. Check out the example below: A 1y ATM call option with 50% volatility is 8% more expensive at 4% interest rates vs. 0% interest rates.

This makes option bets less attractive. Just like collapsing demand for credit crashed the housing and automotive industries in 2022, it also crashed demand for LEAPS. Nobody wants LEAPS anymore. You can see that in the pitiful IVs exhibited in theTSLA 0.00%↑ option chain for example.

But people still want to engage in options trading. So they engage in 0DTE options. It is hard to believe that these options cause systematic risk. Even if they account for 40% of option trading volume, their actual structural impact on leverage is tiny because they are gone at the end of the day and capital needs to be deployed again. A 365D ATM 50% IV call is about 20x more expensive than it’s 1D version. 0DTE are toothless tigers from a financial stability point of view.

Sincerely,

Your Fallacy Alarm

GREAT JOB/ANALYSIS!