What is cash on the sidelines?

Don't look at the absolute amount of cash and cash equivalents in circulation if you want to gauge how much buying power there is. Look at them relative to stock market capitalization.

TLDR Summary

The total amount of money market funds outstanding is not cash on the sidelines. It can’t be converted to stocks by investor choice because every seller of a money market fund needs a buyer.

It’s better to think of low risk assets as collateral for high risk assets. The higher the ratio between the outstanding balances of low risk and high risk assets, the more ‘safe’ assets investors have in relation to their ‘risky’ assets and therefore the more potential there is for them to seek more risk in their portfolios.

Specifically looking at money market funds and the US stock market, this ratio currently sits at its 12% percentile when benchmarked against the last forty years. It’s a data point indicating above average risk appetite right now.

Record high money market assets

Take a look at this X post:

The chart plots the total balance in money market funds and the post highlights that it currently sits at an all-time high. What’s most interesting here is what people comment on it. The post has attracted 248 comments, many of which are framing this as ‘money on the sidelines’, implying a highly bullish interpretation.

This is not the first time I have come across such a post with that level and direction of engagement. It’s happening all the time. It’s spread by investing celebrities. And it’s utterly misguided.

For every buyer there is a seller

No investor can raise or drop the amount of debt securities out there by rotating into or out of them. When someone sells, somebody else has to buy. If all these investors would choose to dump their money market funds to buy stocks, stock prices may moon, but the total money market fund balance will stay completely unchanged.

The only way for the money market balance to grow is when issuers decide to issue money market instruments. And this decision depends on their borrowing appetite and their interest rate expectations.

The US government obviously dominates the issuance of US Dollar money market instruments because of their sheer endless desire for deficit spending. And they have heavily focused on issuing short-term paper in recent years. Historically, Bills have accounted for 10-25% of Treasury net issuance. During the last three years, they have accounted for 45%. This has increased the total outstanding balance of Bills from 15% to 20% of all Treasury debt.

This balance now amounts to $5.8tn, 65% higher than three years ago and 140% higher than at the time when the pandemic started.

Between June 2022 and June 2025, the amount of Bills outstanding has increased by $2.1tn. Over the same period, the money market fund balance has increased by $2.4tn. So, about 90% of the increase in money market funds can be explained by the debt issuance of the Treasury. The rest is private sector borrowing and the Fed’s quantitative tightening.

Generally speaking, if there is a need to borrow (whether it’s from the government or from corporate borrowers), the borrower’s term choice depends on both their own preferences and the preferences of their lenders. The more issuers expect falling rates, the more they will issue short-term debt as opposed to long-term debt. And the more lenders expect falling rates, the more will they demand long-term debt (and hence give issuers more attractive terms on that).

So, when the issuance of short-term debt securities outpaces the issuance of long-term debt securities as they have done recently, there are two possible reasons (or a mix thereof):

Borrowers expect falling rates and therefore deem short-term borrowing more attractive than long-term borrowing.

Investors don’t expect falling rates and therefore deem short-term lending more attractive than long-term lending.

This framing actually allows for a bearish interpretation of the surge in money market debt outstanding. If it is actually driven by investor demand for short-term debt instruments, it means that investors do not expect falling rates. And if they do not expect falling rates, it means that they expect continued economic strength. And if they expect economic strength in excessive numbers, there may be a pain trade in the making proving them wrong.

But that is just speculation. We don’t know and can never know for sure whether the US government is issuing Bills at this scale to satisfy a market need or whether it is simply a political decision that investors just swallow.

A better way to look at it

Like any form of debt, securitized debt is a financial asset, i.e. a claim on a payout from someone in the future. The sooner that payout is scheduled and the more trustworthy the counterparty, the lower the risk associated with that payout. And the lower the risk in a financial asset, the more ability and incentive for its owner to seek risk elsewhere. Investors/lenders can’t change the amount of financial assets in circulation. But they can use them as a collateral to buy other assets.

I hope that this framing makes it obvious that we should not look at the total amount outstanding of any type of financial assets, such as physical cash, bank deposits, money market funds or even all debt outstanding. Instead we should put them in relation to the asset class that we deem a suitable addition to the portfolio of someone owning those financial assets.

Bills are particularly powerful as a collateral for risk assets as evidenced in the chart below that plots the annual Bill issuance against the performance of the S&P 500.

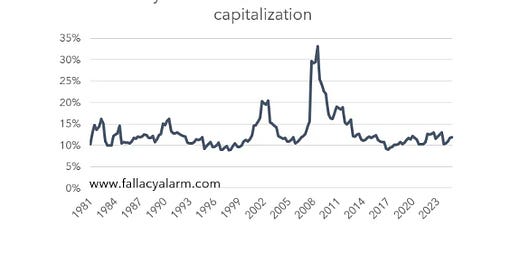

To make the observation from the intro above more meaningful, we ca can divide the total money market funds balance by the total US stock market capitalization. The higher this ratio, the more ‘safe’ assets investors have in relation to their ‘risky’ assets and therefore the more potential there is for them to seek more risk in their portfolios.

It’s certainly not a market timing tool and there was more noise than signal in it at times. However, it does somewhat help to gauge the risk/reward profile of any given market. The peaks in the early 80s, 90s, 2000s and in 2009 were great moments to buy. Right now, the metric is at quite low level, in fact it’s lower than for almost 90% of the time since 1985. That’s not a sell signal in itself. Great stock market returns have followed similar levels in the past. But it certainly doesn’t jive with the ‘cash on the sidelines’ narrative often spread by people posting the money market funds balance.

Sincerely,

Rene