🔎Biotech Compendium: RNA therapeutics

Is there a promising commercial future for programming biology without editing DNA?

What is the Biotech Compendium?

A couple of months ago, I started a new series of posts which I dubbed the Biotech Compendium. It’s an attempt to provide a clear and comprehensive roadmap for the biotech sector, its key players, and the most promising technologies.

I believe having such a primer will be helpful for any investor looking to capitalize on the innovation in this fascinating industry once it’s back in fashion. Biotech has had a tough couple of years. But its long-term prospects continue to be amazing and 2025 has proven to be the year where financial markets once again woke up to that.

The first edition of the Biotech Compendium covered gene therapy with a special emphasis on gene editing.

Gene editing is possibly the industry’s boldest technological frontier. The traditional method in biotech is to reprogram microbes to make them produce molecules that have therapeutic functions in our bodies. Instead of producing those molecules externally, CRISPR and related methods attempt to rewrite our DNA to produce these molecules directly inside of us. This technology promises medications that are more powerful and more lasting than the traditional approach. In theory, a single dose can fix a genetic disorder permanently.

Today’s second edition of the Biotech Compendium will cover RNA therapeutics. This technology also attempts to reprogram what our cells do, however without permanently altering our genome. The pandemic made this technology first famous and then infamous. Below I will investigate whether this technology has a promising commercial future despite the limitations revealed during and after Covid. I will also profile the industry’s key players, some of whom are writing fantastic success stories right now.

More recent biotech and healthcare content from Fallacy Alarm

TLDR Summary

Traditional biotech is about altering the genome of microbes to make them produce molecules that have therapeutic benefits once administered to our bodies. It’s a powerful approach that started revolutionizing medicine forty years ago. It does have limitations though. Most importantly, it merely counterbalances the effects of faulty internal processes rather than fixing them. Many disease-causing proteins operate inside cells where they are inaccessible for these biotech drugs.

DNA- and RNA-based therapies are attempts to overcome the shortcomings of this traditional approach by reprogramming activity inside the patient directly to trigger, suppress, or correct protein production. Protein production is the central function of most body cells. Correcting this function therefore has massive potential to develop much more capable therapeutics.

RNA-based therapies differ from their DNA-based counterparts (such as CRISPR-Cas) in that they don’t permanently alter the cell’s operations. This makes them easier to control and it lowers long-term risks for the patient. As a result, drug developers can move faster and potentially unlock new and broader use.

The pandemic made RNA technology first famous, then infamous. It highlighted its capabilities and then its shortcomings. Most importantly our natural immune reaction to free and abnormal RNA. First and foremost, an inflammation demonstrates that our immune system is working. But it also comes with costs for our cardiovascular, metabolic and neurological health. Addressing tolerability issues associated with immune system activation is the central challenge for RNA therapies.

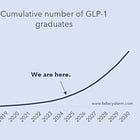

While the technology is forgotten and scorned by many investors, various RNA companies have silently made tremendous scientific and commercial progress recently. mRNA players like Moderna and BioNTech are not the industry’s poster children anymore. It’s not about making respiratory vaccines. It’s about fixing various rare genetic, hematological, cardiometabolic and neurological diseases. RNA drugs might even play a role in cancer therapy and obesity soon, the two most sought after biotech segments.

Several companies have recently transformed from long shot ideas to technology platforms with a convincing track record of churning out approvals of commercially promising drugs. M&A activity has picked up as well. Big pharma companies are busy grabbing the industry’s most promising assets.

RNA may feel less scientifically exciting than CRISPR-Cas. But it may be more investable as a theme right now. The technology is much more mature, possibly five years or more ahead. It feels that the technology is ready make commercial strides which may make returns for investors more robust and sustainable.

How does RNA work?

A cell is a self-contained functional unit of an organism. Its two main functions are to a) convert nutrients into energy and b) use that energy to make proteins (for example hormones for messaging, enzymes as process catalysts, structural proteins for the body such as collagen).

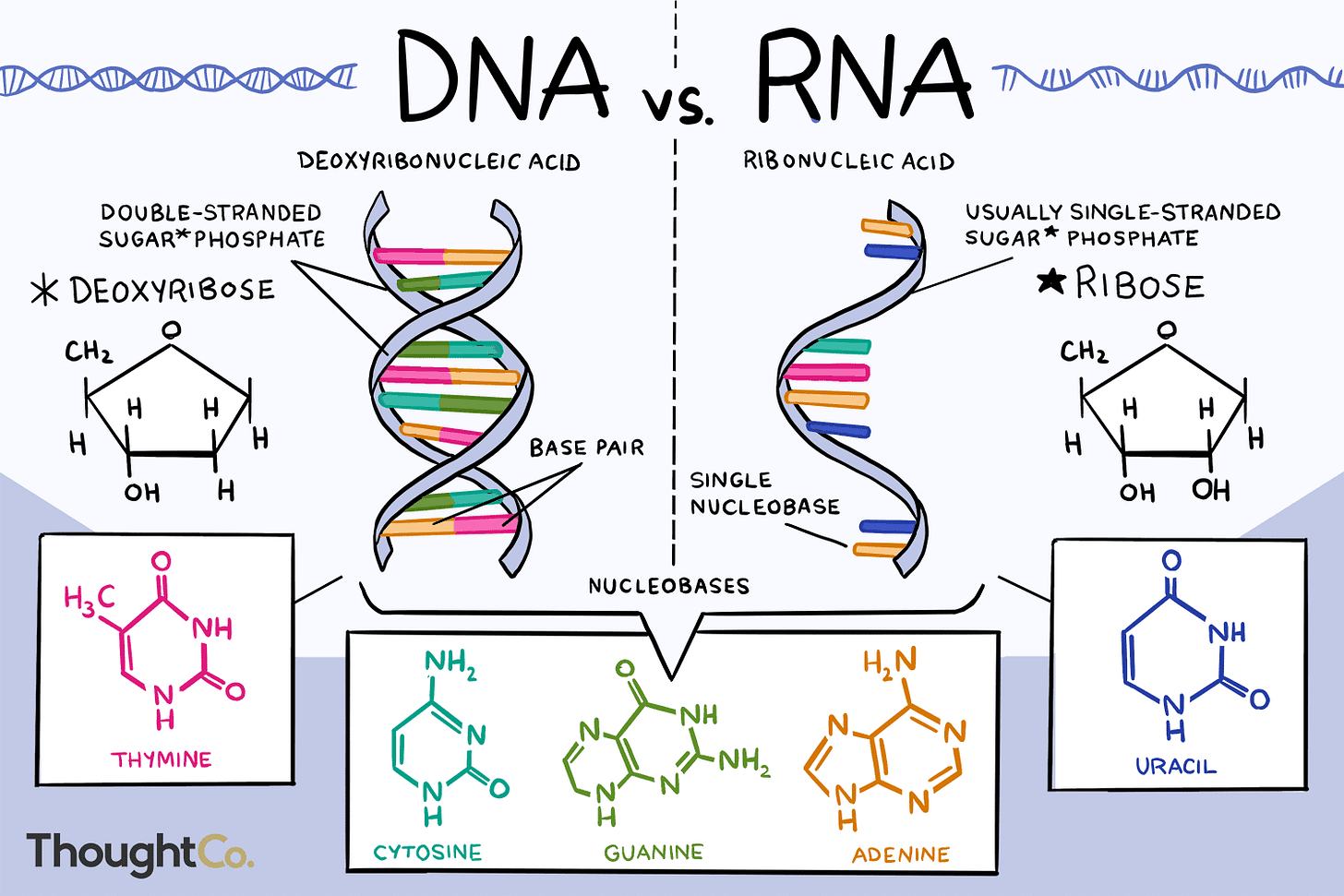

DNA is the famous double-helix in the nucleus of the cell that serves as the master manual for the cell to carry out its functions. When a cell needs to do something, it copies a specific gene within the DNA into an RNA, which looks like DNA, only usually with just one strand.

The purpose of this RNA is to leave the nucleus and go into the cytoplasm (interior working space of the cell) where ribosomes (protein-making machines) read it and then assemble the protein as instructed in the RNA. This is why an RNA for this purpose is called a messenger RNA (mRNA).

This is where RNA therapies come in. They are about manipulating this process in various different ways to achieve positive effects. Examples include:

mRNA drugs: provide a synthetic mRNA that instructs ribosomes to make a protein. They add new instructions.

Antisense drugs: bind to natural RNA to block, destroy or reprogram it to fix a faulty process. They block or fix existing instructions.

siRNA: Trigger natural RNA-destruction to eliminate unwanted protein production. They destroy existing instructions.

RNA is broken down once its job is done. This is deemed an important advantage of RNA-based medicine over DNA-based medicine such as CRISPR. Both therapies manipulate the actions of our cells. But the RNA manipulation is temporary. This makes the technology easier to control and it poses lower regulatory risk, which in turn enables drug developers to iterate faster in terms of candidate design, manufacturing, testing, modification and repeat. RNA’s transient nature is both a decisive feature and one of its two most important bugs because it makes its effects less durable.

The second bug is the organism’s natural immune reaction to free RNA. Our immune system throws a tantrum when it encounters free or abnormal RNA because its usually evidence for a viral infection. Viruses typically make RNA to instruct ribosomes to make more of them. Hence, the immune system activates once it finds the RNA medicine. The body heats up. Blood vessels widen to increase blood flow to the infected areas. Swelling occurs because vessels are made leaky to allow immune cells to leave the bloodstream and reach the infected tissue. Pain and fatigue signal that rest is needed. We commonly summarize these symptoms as inflammation.

Inflammation first and foremost signals that the immune system is working. But it also comes with a cost. Normal body function is disrupted. The cardiovascular and metabolic system gets under pressure. If it becomes chronic, inflammation is even associated with higher cancer risks and negative neurological effects.

The central crux of RNA-based therapies is this: To achieve lasting therapeutic benefit, many RNA drugs require repeated administration which is challenging due to the issues with persistent immune activation.

History

Pre-Covid

RNA technology is actually quite old. It was discovered in the 1960s and 1970s around the time when recombinant DNA technology launched the biotech industry. First experiments with synthetic mRNA happened in the 1980s. Then progress stalled until the late 1990s. The technology worked in animal tests. But to become relevant in medicine, two crucial challenges had to be overcome: the RNA tended to degrade too fast and it tended to cause overly strong immune system reactions.

The first RNA-based medicine was approved in 1998. Fomivirsen was developed by Ionis Pharmaceuticals IONS 0.00%↑ and commercialized by Novartis. It was an antisense drug that treated cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in AIDS patients by blocking the protein production required for viral replication.

As the first RNA-based medicine, fomivirsen was a technological breakthrough. But commercially, it was a dead end. It came with significant side effects (eye pain and inflammation), it was expensive, and it was quickly made redundant when new HIV therapies restored immune function and sharply reduced CMV infections.

Several more antisense drugs were developed and approved later. Mipomersen was approved in 2013 for LDL cholesterol. It was also developed by Ionis and commercialized by Genzyme (today owned by Sanofi). It prohibits the production of a protein essential for LDL cholesterol production. It failed commercially because of toxicity concerns and because alternative therapies arrived that were more effective and safer.

Nusinersen was approved for spinal muscular atrophy in 2016. It was also developed by Ionis and commercialized by Biogen BIIB 0.00%↑. Nusinersen corrects faulty RNA processing so that cells produce the correct version of a critical protein needed to preserve and improve muscle function. With peak revenues of roughly $2bn in 2019, nusinersen became the first true commercial success of an RNA drug as it dramatically improved outcomes and survival, particularly when administered early.

The first siRNA drug to get approved was patisiran in 2018 for a rare genetic disorder called hATTR. It was developed and commercialized by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals ALNY 0.00%↑. hATTR damages nerves due to an abnormal protein produced in the liver. Patisiran destroys the RNA that instructs the production of that protein.

A central tool to make siRNA-based therapies possible is RNA interference (RNAi) which was discovered in 1998. It is a natural cellular mechanism that silences specific genes by destroying or blocking their mRNA, thereby preventing protein production. Scientists use this natural pathway for their drugs.

By the eve of the pandemic, RNA technology had become technologically and commercially somewhat proven, but was still fragile without ultimate validation. It wasn’t in primary care yet. Revenues were modest. And it remained unproven whether it could be commercially manufactured at scale.

mRNA in particular remained commercially unproven. Not a single mRNA drug had been approved by the end of 2019. Adding new biological activity like mRNA does is much harder than modifying or reducing existing activity like siRNA and antisense drugs do.

Then Covid entered the stage. And changed everything.

Covid

Traditional vaccines rely on growing an attenuated or inactivated live version of the virus which typically takes months to years with limited predictability. The public demanded a faster solution in 2020. mRNA vaccines only require the genetic sequence of the virus because all biology can be outsourced to the patient’s own cells. This meant it was possible to design the vaccine within days and move to trials pretty much instantly.

Combined with the massive public interest, this led to an unprecedented pace of vaccine development. The first approvals happened in December 2020, less than a year after development started.

Investors were amazed to see this and RNA stocks went stratospheric based on the expectations that RNA would prove to be a platform technology and revolutionize various verticals of drug development. Subsequent returns were then devastating for two main reasons.

Firstly, the vaccines ended up much less efficacious than originally hoped. The virus evolved way too fast for the vaccines to handle. Its surface protein mutated rapidly and rendered the vaccines ineffective. I don’t doubt that vaccination helped avoid severe disease and hospitalizations. But from a PR perspective, these efficacy challenges and calls for the umpteenth booster were a disaster.

Secondly, mass vaccinations also put the key challenge of RNA technology into the spotlight: Tolerability issues associated with the immune reaction mentioned earlier. Side effects of these vaccines were significant. In some cases severe. This very much tainted the reputation of RNA technology. Many people even labeled it experimental gene therapy.

I don’t think that term is quite accurate because mRNA vaccines don’t integrate into the genome under normal physiological conditions. However, as mentioned earlier every immune reaction comes with health risks because it causes collateral damage in the organism.

Inflammation shouldn’t be triggered carelessly as a therapeutic means. It comes with a cost which has to be compared to the benefits. Health risks of a Covid infection were negligible for many patient groups. It was irresponsible of policymakers and the RNA industry to brush off concerns about that. Many were coerced into a medical treatment they were not convinced of. As a result, the technology lost of a ton of credibility. And investors lost a ton of money.

The potentially good news in this mess is this: The poor sentiment might actually present an opportunity for cool-headed investors coming in after the hype. In spite of all the disappointment, RNA technology has proven one thing in the last six years: It can develop and commercially scale therapeutics fast. The pandemic was not the best application to demonstrate the merits of this technology because of rapid virus mutation and because careless mass administering exposed tolerability issues. But there may be lucrative applications in a narrower and more realistic way.

Let’s look into some of those applications by studying the industry’s most important companies.