🔎Cal-Maine Foods: We need eggs.

Protein is our supernutrient, which makes eggs a superfood. Egg prices are volatile due to supply shocks such as the current bird flu. Cal-Maine can take advantage of that via operating leverage.

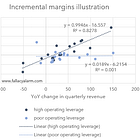

Cal-Maine Foods (CALM) was on my operating leverage list from a month ago. It caught the attention of some readers which is why I am dedicating an article to this company.

The following will not only be interesting for you from an investing perspective. It will also give you some food for thought on your nutrition.

The great German philosopher Oliver Kahn once said: “Wir brauchen Eier.”

I wholeheartedly agree. In fact, the whole world agrees. For several different reasons as I will outline below.

TLDR Summary

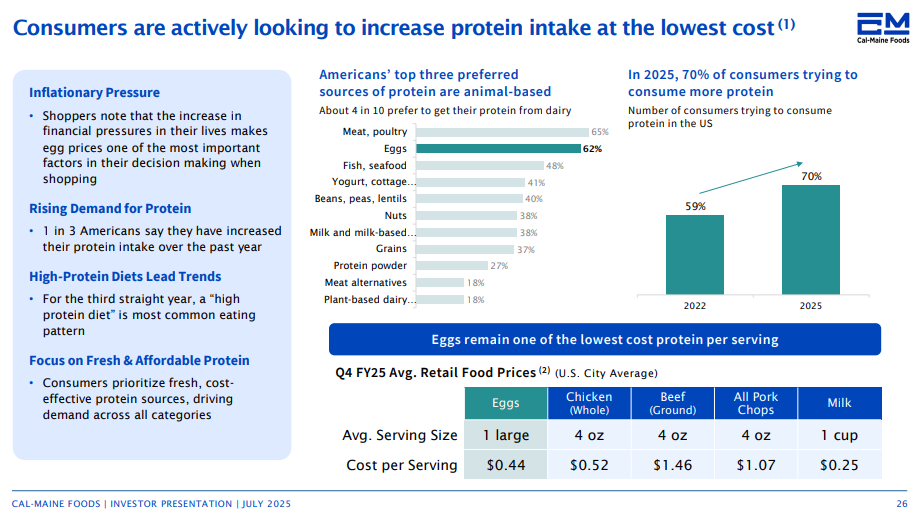

Protein is our supernutrient. It’s the most satiating of all three macronutrients. It stimulates hormones which reduce appetite and make meals feel more filling. It stabilizes blood sugar by slowing digestion. It’s literally a GLP-1 drug. From gym rats to couch potatoes, everyone is hyped up about it.

That makes eggs a superfood. They are the highest quality natural protein source out there. They provide all nine essential amino acids with near-perfect proportions for human needs. Eggs are the protein standard against which all other protein sources are benchmarked. In the German language, egg white is literally the colloquial term for protein. Eggs also need very little processing which preserves nutritional quality (especially compared to plant-based protein). And they happen to be very affordable, even with recent price surges.

Cal-Maine Foods (CALM) is the largest egg producer and distributor in the US and has consolidated the industry for decades organically and through acquisitions. They are vertically integrated and own 14% of the US market.

One of the most exciting aspects of the business is the company’s extraordinary operating leverage. In conjunction with the notorious volatility of egg prices, this can create years with astronomical earnings. In FY25 (which ended in May 2025) they earned $1.2bn, a third of their entire market cap.

This is particularly interesting given the current global circulation of the bird flu that keeps causing outbreaks in poultry populations. This panzootic (that’s the animal equivalent of a pandemic) is going into its fifth year and there are no signs that we’re getting it under control. Birds are dropping dead from the skies all over the world in an unprecedented manner. It’s a huge crisis that is for the most part happening without awareness of the general public.

It will take years to fully rebuild the national flock. As long as the supply shock persists, CALM will continue to overearn cyclically . At some point the company will have generated its entire market cap in extra earnings. The investor will then get the terminal value of the business on top for free.

Our journey to understanding protein as a supernutrient…

Eating proteins is good. That’s probably one of the few things everyone agrees on across all the different diets out there.

This strong consensus on the importance of proteins wasn’t always so. Nutritional philosophies emerged in the early 20th century and emphasis shifted with time. Initially, people obsessed about vitamins and minerals, i.e. micronutrients that the body needs in tiny amounts to ensure a proper metabolism. Pharma companies started mass producing these vitamins and food manufacturers started fortifying their products, such as cereals, breads and milk. They still do so to this day.

After World War II, large parts of the developed world quickly moved into food surplus territory. As a response, nutrition science shifted from ensuring adequacy to managing excess. Most importantly, fats were identified as the central culprit for heart disease, which became the leading cause of death around 1950.

A series of studies in the 1950s and 1960s linked saturated fat and cholesterol consumption to heart disease and highlighted the benefits of plant-based, low-fat diets. Vegetable-oil producers capitalized on this narrative to market their products as healthier substitutes.

The vilification of animal fats required to replace them with other macronutrients to use as primary fuel for the body. In principle, those can either be carbohydrates or proteins.

Proteins were (and still are) much more expensive than carbohydrates. Many protein sources were also linked to the same foods that were high in saturated fats. And they were at that time not primarily viewed as an energy source, but rather as building blocks to repair and grow tissues and make enzymes and hormones. The human body can convert proteins into energy, but not as easily as carbohydrates or fats.

Proteins can be broken into amino acids upon ingestion and some of those can then get converted into glucose to be used for energy (gluconeogenesis). But that’s a quite energy intensive and inefficient process. And in protein form they can’t be easily stored for later energy needs like carbohydrates or fat can. When proteins are not immediately metabolized, they mostly become building blocks of the body. Using them for energy generation later would mean to break down tissues, which the body would only do in emergencies such as fasting or starvation.

In contrast, carbohydrates can be easily stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles and can quickly be converted back into glucose for energy. Even more so than fats which are stored as triglycerides in fat tissue and than broken down into ketones for energy.

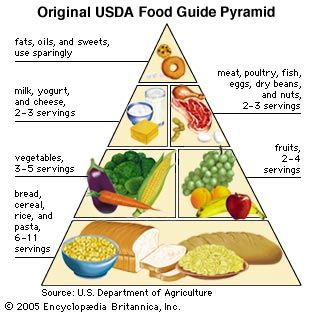

For these reasons, carbohydrates emerged as the preferred macronutrient.

This approach quickly backfired. Refined carbohydrates began their triumphal march into our kitchens and onto our plates. Eating them causes rapid spikes in blood sugar and insulin. Hunger returns quickly after eating. They also promotes fat storage. With excess sugar, the body stops burning fat and even starts converting the excess sugar into additional fat (de novo lipogenesis). Calorie intake surged. And health issues such as obesity and diabetes surged with it.

As a result, the diet debate started shifting from fats vs. carbs to calorie counting in the 1970s and 1980s. Nutrition experts argued that it’s not the type of calorie, but the calorie itself that is the problem. Companies started to market their products not only as low fat, but as low fat, low sugar, low calories. They still do so to this day.

Then proteins entered the nutrition stage in the 1990s and 2000s and became the supernutrient: They provide the body’s building blocks to preserve muscle mass even with caloric deficit. They enable the production of hormones, enzymes and immune molecules. Proteins are the most satiating macronutrient. They stimulate secretion of hormones which reduce appetite and make meals feel more filling. They stabilize blood sugar by slowing digestion. They are literally GLP-1 drugs. 😉

To be fair, some people are overdoing the idea of a high protein diet. They starve their bodies of carbs and fats. The lack of carbs and fats can result in fatigue and low endurance. Excessive protein digestion can be a strain on certain organs such as kidneys and liver. And it makes the body more susceptible to dehydration (glycogen binds water). But as long as it happens within a reasonable range, a high protein diet is conducive for a healthy life.

…made us realize that eggs are a superfood.

Protein quality

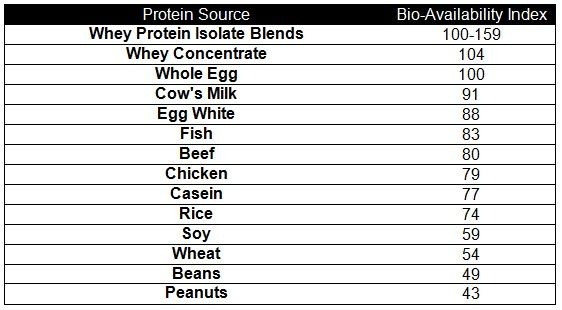

Eggs contain the highest-quality protein in nature, about 6-7 gams per egg with near-perfect proportions of the nine essential amino acids for human needs. These amino acids are foundational for nearly every process in our body.

The nutritional value of eggs is so high that it’s used as the reference standard against which all other proteins are measured. Every natural source of protein is expressed as a percentage of eggs. In German, egg white is literally the colloquial term for protein.

In addition to being a superior protein source, eggs are also rich in micronutrients, such as Vitamin B and D. They have barely any carbs, rather little saturated fat and very little sodium. They check many boxes that health conscious consumers are looking for today. The GLP-1 boom is a tailwind for them. We can’t say that for many other foods.

Affordability and accessibility

In light of their nutritional value, eggs are surprisingly affordable. Per the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average cost of a large egg was $0.30 in August 2025. This study argues that “eggs are cost efficient. When comparing the relationship between foods on the basis of calories and unit cost, the energy cost of eggs is significantly less when compared with that of other animal-protein foods such as meat, poultry, and fish.”

Specifically with respect to protein, $0.30 per egg equates to about $0.05 per gram of protein which is roughly on par with less optimal protein sources such as chicken breast and ground beef and it’s about half the price of fish and steak. It’s also on par with whey protein powder which raises the question why we even bother with such highly processed artificial sources of protein.

In addition to cost considerations, eggs are also accessible and practical. They require minimal processing and they are easy to transport and store.

Role of cholesterol

A large egg typically has about 373mg of cholesterol per 100g, which is quite high, higher than butter (215) for example and much higher than most meats (80-100). This taints the reputation of eggs due to cholesterol’s link to heart disease. Cholesterol can build plaques in arteries, triggering inflammation and hinder blood flow.

However, numerous studies have shown that cholesterol intake typically only has a minor effect on blood cholesterol in most people. More important determinants include genetics, saturated and trans fat intake, body weight and lifestyle.

To the extent a consumer is concerned with cholesterol, they can avoid the yoke and simply consume the egg white (which even has a higher protein share than the yoke).

Sustainability

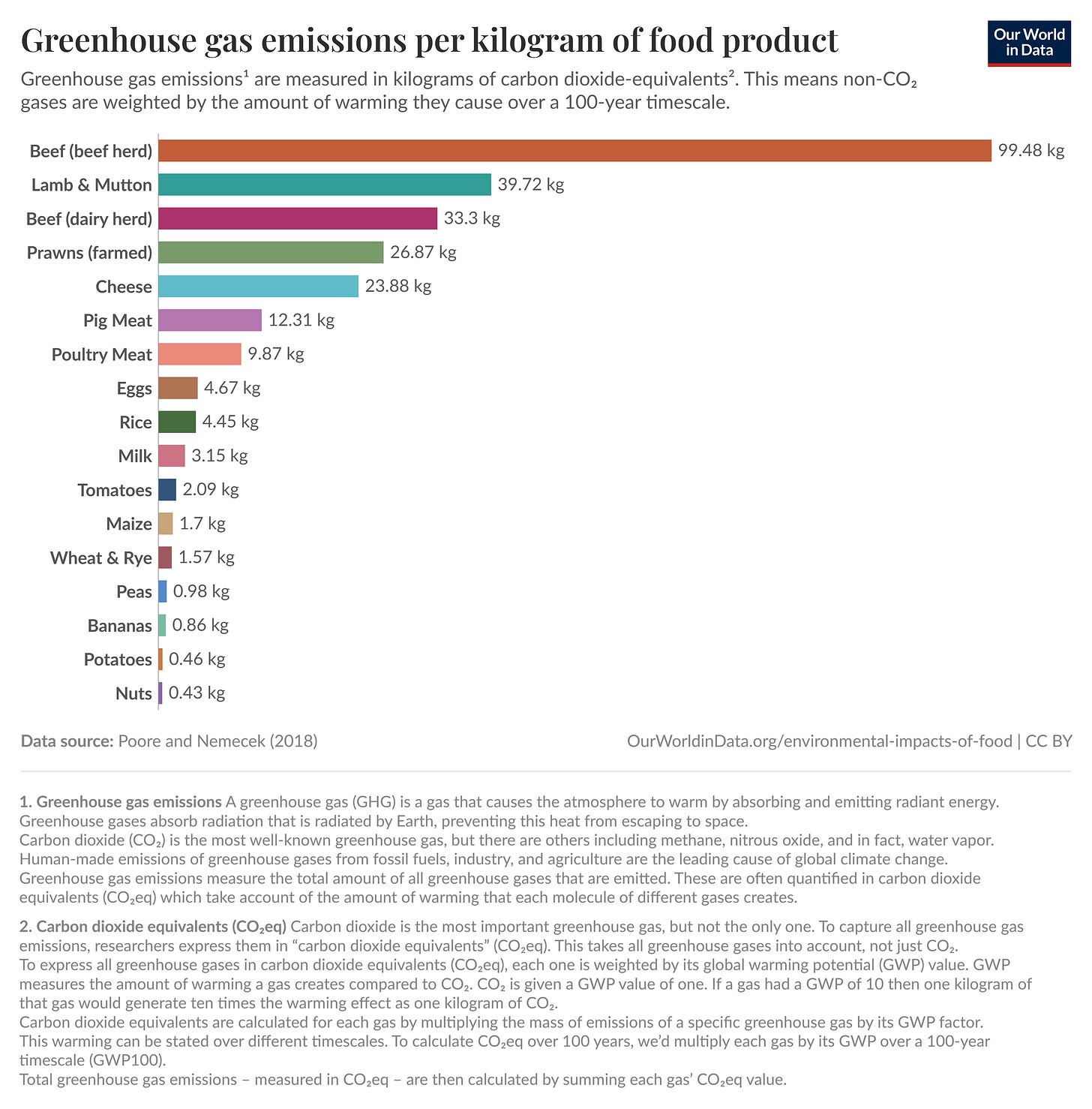

Eggs are not only a high quality and affordable source of protein. They also come with relatively low environmental costs. Production doesn’t need much space, feed efficiency is high (about 2kg feed per 1kg of eggs, a crazy ratio, isn’t it?) and they can be produced virtually anywhere in the world.

Per Our World in Data, producing one kilogram of eggs emits 5kg of carbon dioxide-equivalents, which is only a fraction of meat, especially beef.

Plant-based proteins are obviously more resource-efficient, but they often offer lower nutritional quality. They often lack certain essential amino acids and non-protein components limit protein digestibility. This is typically addressed through increased food processing which can lead to lower overall nutritional quality.

For all these reasons, it’s unsurprising that consumers are looking to increase their protein consumption and that they are looking to do so via eggs.