How to create the 2025-2027 stock market bubble in four simple steps

Rate cuts are coming because they are inevitable. This will launch a credit boom in the private sector that is loaded to the gills with savings. New financial excesses seem inevitable.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not and should not be construed as investment advice. This is my investing journey and I simply share what I do and why I do that for educational and entertainment purposes.

This article is entirely free to read.

The time horizon of my macro coverage is usually about a year. In my experience that is the cadence at which markets cycle through sentiment and positioning imbalances.

Today, I want to dare to make a longer term prediction. I want to outline a scenario that I believe to be the most plausible path for global financial markets for the remainder of this decade.

TLDR Summary

It may sound odd after the strong stock market performance recently, but we are quite possibly on the eve of the formation of a major bubble that could catapult the S&P much higher over the coming few years. The Fed will have to walk back its rate hikes eventually because they do very little with respect to their actual goal of draining liquidity from the financial system.

Years of excessive fiscal spending (both primary and aided via rate hikes) have created the largest private sector savings injection the world has ever seen. Private sector savings serve as the collateral for private sector borrowing. The more savings there are in the private sector, the more likely its members are to consume and invest.

Japan in the 1980s serves as a somewhat unexpected blueprint for this mechanism. They used their savings from their trade surplus to launch a debt binge when the BoJ lowered rates in 1986. Likewise, US households have high savings today from fiscal deficits in conjunction with historically moderate trade deficits.

Due to a) the lack of rate sensitivity in the private sector and b) fears about financial excesses, I expect the incoming cutting cycle much more gradual than the last few ones. These rate cuts will provide steady fuel for the business cycle that is just emerging from a major trough.

Whether or not that will trigger the formation of a full-sized bubble depends on whether this business cycle comes with a suitable narrative to drive optimism and exuberance. ‘AI’ is a candidate for such a narrative.

The demographic setup may provide additional support. Millennials, the largest US generation in history (and perhaps ever) are entering into prime risk asset buying age right now. When their boomer parents were at a similar age, they caused dotcom.

By hiking like maniacs, policymakers have cornered themselves. Every day that passes without cuts will fuel private sector savings even more, loading the gun even more. Eventually they have to stop this vicious cycle. The sooner the detonation of the 2020s savings bomb the smaller it will be and the less detrimental its inevitable aftermath will be.

Step 1: Manipulate rates to zero to allow people to lock in cheap debt for decades and make them immune to rate hikes.

Long-term interest rates naturally gravitate towards nominal economic growth. I have talked about this at length before. It’s because savers and creditors require a) inflation protection and b) compensation for opportunity cost of not participating in risk asset returns. And a beautiful side effect of ‘rates = growth’ is that liquidity compounds at the same pace as GDP which implies constant productivity of liquidity.

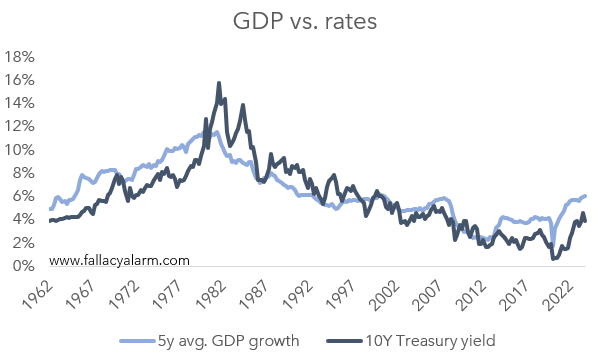

Don’t take my word for it. The chart below compares the 10-Year Treasury yield to the average annual GDP growth over the preceding five years:

The high correlation between both metrics should be immediately visually apparent. Sometimes, they diverge. This can happen for two reasons. Either markets over/underestimate real growth and inflation. For example, rates were too low for much of the 1970s which made bond holders earn subpar returns. Or it can happen when policymakers manipulate rates above or below their fair level. This happened for example in the 2010s and early 2020s when ZIRP and QE manipulated bond yields way below the 4%+ at which GDP advanced.

QE (i.e. the buying of financial assets with freshly printed central bank money) is often referred to as money printing, i.e. liquidity creation (as you know I prefer the term ‘liquidity’ over ‘money’). But the Fed cannot create real liquidity. When they buy Treasury securities, they simply create bank reserves. If the bank doesn’t do anything with these reserves, nothing with economic relevance happens.

Liquidity creation happens when someone issues debt and does something in the economy. This is most importantly the government, but it can also be a private sector issuer.

Of course, the Fed’s actions are not irrelevant. They can indirectly influence liquidity by manipulating rates which then impacts the pace of the fiscal and the credit impulse. Changing overnight rates is the most direct rate manipulation. QE is a more indirect version. QE is first and foremost interest rate manipulation, not liquidity creation. If you are interested, I went into great detail on monetary mechanics in the article below:

The ZIRP + QE age coincided with a lengthening of the duration in private sector debt. Home mortgages are one of the most important debt segments. US households have a total balance of $13tn outstanding which is about 70% of their total liabilities.

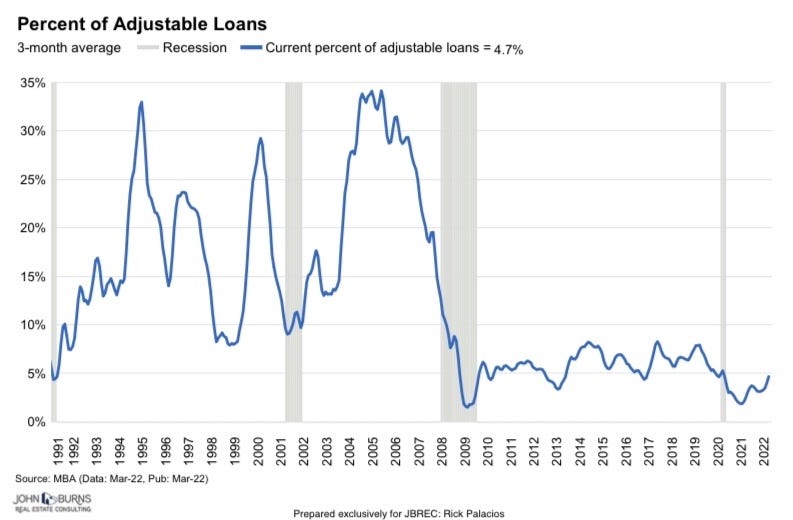

Before the GFC, it was customary for many mortgage borrowers to enter into variable rate loans. About a third of all loans were adjustable. Today, that percentage is way below 10%.

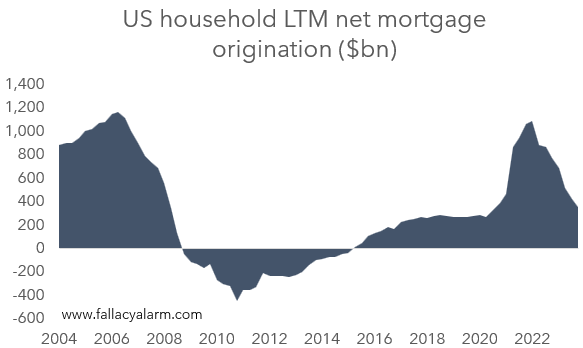

During the pandemic years, US households took advantage of ultra low mortgage rates. The annual run rate of net mortgage origination peaked at $1.1tn in 1Q22, just before the rate hikes started.

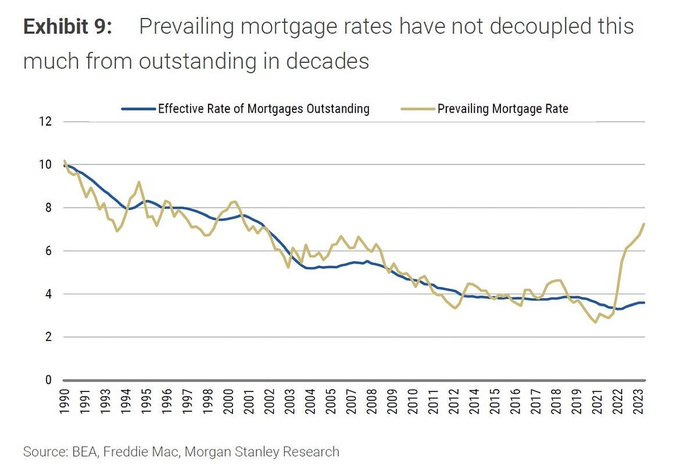

As a result of the mortgage duration increase and the 2020/21 borrowing spree, the effective rate of mortgages outstanding it very sticky compared to the prevailing mortgage rate.

This also explains why rate hikes have done nothing to mortgage delinquencies so far. It will take many years for rate hikes to show up here:

The result is that traditional monetary policy is largely useless for two reasons. Firstly, rate hikes do very little in terms of deterring US households from consumption.

And secondly, rate hikes are very ‘effective’ in causing bank instability. Someone has to bear interest rate risk. If it’s not the borrowers, it’s the lenders, which are typically the banks. This is a very unwanted byproduct of rate hikes because it ties the Fed’s hands. Restrictive monetary policy tends to nuke the banking sector before it can do its wanted harm to household spending.

Step 2: Run monstrous primary deficits to flood people with savings.

When the government runs a deficit, they hand out money that ends up as private sector savings one way or another. It’s a trivial statement that is obviously true. Yet, so many people struggle with thinking through the ramifications entirely.

Treasury debt is not our debt as citizens that we or our children have to pay for. The issuer and debtor is the US government. Citizens are the creditors, not debtors. Can they lose in this game when excessive deficits cause inflation? “Even if our children don’t pay the debt down explicitly, they will pay via inflation”. That’s the argument I hear often. Of course, inflation can occur as a result of deficits and it can hurt people with claims against the Fed or the Treasury. But nobody forces anyone to hold their savings in the form of US Dollars or US Treasuries. It’s a choice.

The private sector (incl. the foreign private and public sectors) is a beneficiary of deficit spending. When the Treasury creates liabilities for themselves, they create assets for everyone else.

In 4Q19, US GDP was running at an annual rate of $21.9tn. 52 months have passed since then. During those 52 months of madness, the Treasury has run a cumulative deficit of $9.5tn. That is about 50% of the entire US GDP as of 4Q19. In just over four years! It’s the greatest savings injection of all time. And it has not even inflicted its full force yet. Because of the Fed’s response to these deficits.

Step 3: Manipulate rates back up to fuel people's savings even more via interest payments.

When inflation surged due to a combination of excessive deficits and lockdown induced supply, the Fed reacted with panic hikes, seemingly not knowing that this medicine was ineffective at best and contra productive at worst.

Ineffective because private sector borrowers have long duration debt as outlined in step 1. And contra productive because rate hikes raise the Treasury’s funding costs which exacerbates deficit spending, the true driver for potential inflation persistency.

The group of Treasury deficit spending beneficiaries goes far beyond domestic households. But they are of course an important group. In the article below, I had estimated that the rate hikes are adding several hundred billion dollars annually to their equity for the time being.

It’s logical. Someone has to receive the $1tn interest expense of the Treasury, right? And even that is a rich guy or someone from overseas, they will have to do something with their interest dollars. Most likely they will reinvest them into the US economy. Either directly or by selling them to someone who will do so.

While rate hikes have limited impact on the cost of existing private sector debt, they have an additional effect with respect to new debt issuance. Everyone who can will not borrow at these levels. Some borrowing gets cancelled. The consumption or investment simply does not happen. But a considerable portion likely just gets postponed. Industries with capital intensive products are dead. Look for example at sales activity in the housing market or in the new or used vehicle market. Loaded springs they are!

Step 4: Normalize rates back down to encourage people to borrow against their huge savings from step 2 and 3 to consume a lot of junk and to buy assets with leverage.

Private sector savings are the implicit collateral for private sector borrowing. The more savings there are in the private sector, the more likely its members are to consume and invest. High interest rates can deter this temporarily. But rates can’t defy gravity forever.

There is a somewhat unexpected historical precedent to this mechanism: Japan in the 1980s.

The 1985 plaza accord famously devalued the USD against other major currencies, most importantly the Yen. The subsequent FX appreciation caused a deflation shock in Japan to which the BoJ responded with rate cuts, fearing for the competitiveness of their export industry. Between 1986 and 1987, they lowered the rate from 5% to 2.5%.

These rate cuts were totally unnecessary. The Japanese economy was in the middle of a golden run due to a perfect demographic structure.

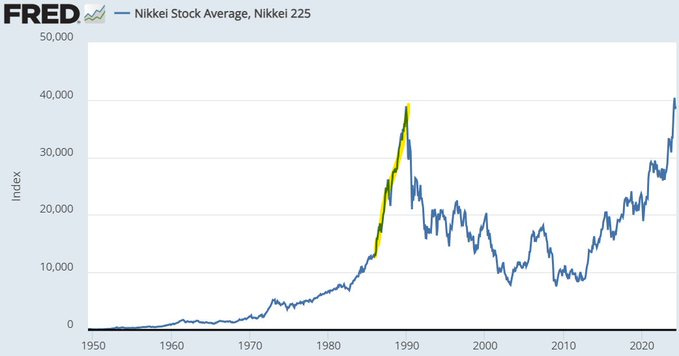

This cheap credit then fueled real estate and stock market speculation. From January 1986 to December 1989, the NIKKEI more than tripled.

The aftermath of those excesses took two decades to be digested! Without those four years of madness, the NIKKEI would not have its weird pattern. It would more resemble the beautiful parabola of the S&P.

Back then Japanese had a lot of excess savings to use as collateral to borrow because their trade surplus was so high. Likewise, Americans have a lot of excess savings today because of the large fiscal deficits in recent years in conjunction with historically moderate trade deficits.

This setup is further aided by the demographic headwinds of the 2010s turning into demographic tailwinds. Millennials, the largest US generation in history (and perhaps ever) are entering into prime risk asset buying age right now.

I believe this is the scenario that the Fed fears with respect to the much anticipated rate cuts. The question is whether they actually can avoid it. By hiking like maniacs, they have cornered themselves. Observing their stupidity inflicts physical pain on me.

Every day that passes without cuts will fuel private sector savings even more, loading the gun even more. Eventually they have to stop this vicious cycle. The sooner the detonation of the 2020s savings bomb the smaller it will be and the less detrimental its inevitable aftermath will be.

Sincerely,

Your Fallacy Alarm

Thank you for this well-argued piece. I think the part of the private sector that will be hurt the most from prolonged high interest rate is the US corporate sector as refinancing will go up from $790bn this year to $1 trillion in 2025, and then 4+ trillion from 2026-2030, according to Goldman. So one way or another as more business closures and commercial real estate loans default, the Fed will have to lower interest rates.

The most basic explanation I have ever seen on how the bubbles are formed through short term debt cycles!