Tracking Fiscal Flows in REAL TIME

There is enormous potential for alpha generation in understanding whether the fiscal debt binge will continue or not. Going forward, I will track this information on a daily basis.

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is not and should not be construed as investment advice. This is my investing journey and I simply share what I do and why I do that for educational and entertainment purposes.

Summary

Going forward, I will closely track and analyze US Treasury deficit spending to observe and anticipate turning points and inflection points that carry market signal. This is the logical next step for me after pounding the table all year long about how fiscal stimulus has become the primary asset price driver.

As of this Friday, the US Treasury has incurred $1.6tn in deficits for the 2023 calendar year so far, which is 68% higher than at the same time last year.

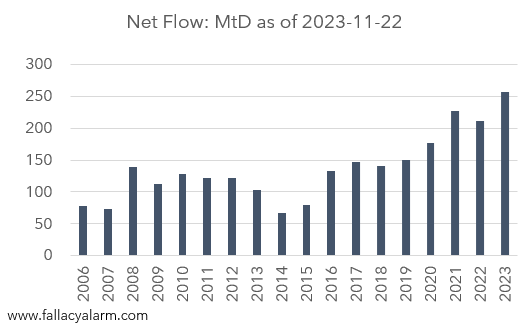

Looking at November 2023 in isolation, the month-to-date fiscal deficit is $257bn, $30bn more than the previous November record of $227bn as of November 22, 2021, which coincided with the S&P all time high that occurred at that time.

The enormous fiscal deficit spending of the US Treasury is in my opinion the main reason why the S&P is up 20% YTD. You don’t often hear me bragging about past calls. I want the focus on the ex ante quality my analysis and reasoning independent of the outcome. But I do consider this a big win for me against the bearish narratives that have persisted everywhere all year long.

The charts above are based on data from the Daily Treasury Statement (DTS) which provides real time insight into some of the most important economic metrics out there.

This article lays the foundation for what data I am going to look at, why I am doing that and what I am looking for in that data. I will refer to this primer in future articles to avoid repetition.

I have built a tool for this purpose, which I call my Daily Fiscal Flow Tracker. This tool allows me to automatically retrieve and visualize the DTS data via an API call. It’s still in a beta phase, which is why I am not yet sharing it with you. I first want to test it properly. I am very excited about this addition to my research toolbox and can’t wait to put it to work in the coming months. You can expect insights from this tool in future macro-related articles whenever it produces signal that is worth bringing to your attention.

Introduction

If you have followed some of my work, you probably know that I view fiscal flows as supremely important as a financial market driver. With public debt levels closing in on 100% of GDP and with deficits north of 6% of GDP, the economic impacts of the public spending cycle dwarf the impacts of the private consumption and investment cycles. The fate of the economy is determined by the spending decisions made by politicians. The decisions made by consumers and corporate executives are secondary.

Debt issuance of any form and any issuer creates liquidity that drives the prices of goods, services and assets. What makes the public sector special is its sheer size. It’s about half of the entire USD liquidity floating around. And as the Fed’s tightening campaign has effectively halted private credit creation, public credit creation has obtained even more relevance.

When the Treasury runs a deficit, it creates private sector savings. These savings will be used for consumption and investment. Wouldn’t it be nice to track this spending in real time to obtain market signals? As it turns account, we can. The US Treasury runs an open book. They inform us about their financial transactions every single day in a data release called the Daily Treasury Statement (DTS). It’s even better than their monthly or annual reporting because it’s their raw spending and revenue data before any accounting massages. It’s all about cash in and cash out. The flows that actually matter.

This DTS consists of various ledgers. The most important one is called Deposits and Withdrawals of Operating Cash. This is the Treasury’s checking account, showing all daily transactions relating to tax receipts, social security payments or interest payments to name a few. We can add these transactions into an aggregate measure, called Fiscal Flow.

What is Fiscal Flow?

In fact, this aggregate measure comes in two versions: Gross Flow and Net Flow. They are defined as follows:

Gross Flow = all withdrawals minus debt redemptions

This is gross government spending. Withdrawals have to be adjusted for debt redemptions because those do not create private sector savings. If the government withdraws cash from their TGA to redeem a bond from a citizen, that’s merely an asset swap for that citizen. Instead of having a claim against the Treasury, they now have a bank deposit. Their wealth has not changed. They will likely not change any spending or investment behavior.

But if that citizen is a government employee and the cash withdrawal is made to pay their salary, then the government has incurred a deficit that creates savings for that employee.

Net Flow = Gross Flow minus all deposits excl. debt issuance

This is net government spending also known as the fiscal deficit. Again, it has to be adjusted for public debt transactions because a deposit due to debt issuance will not drain savings from the private sector.

An alternative way to derive Net Flow is by deducting net deposits from net debt issuance. To the extent debt issuance just lands in the TGA, it does not create a Fiscal Flow. It must be spend on a good, service or asset purchase. Same formula, just rearranged in case it is more understandable.

I tend to focus on Net Flow. When I use the word “spending’, I typically refer to net spending. But both Gross Flow and Net Flow are important and worth tracking. Gross Flow can often be viewed as an initial impulse with follow-up effects on tax receipts. Withdrawals lead deposits you might say.

Who is the government? Are we?

When thinking about the economy, it has helped me to view the government simply as a corporation with the mandate to set and enforce the law in a jurisdiction. When politicians issue debt, they do so in the name of that corporation, not in the name of the people. One of the objectives of that debt issuance is to provide the people (aka the private sector) with a vehicle to save. The private sector (including the foreign public and private sectors) has a desire to save in Treasury securities. Government spending facilitates that desire.

If the government spends less than what the private sector desires to save, that could be called contractionary or restrictive fiscal policy. The private sector will then reduce consumption and investment in an attempt to fulfill their savings desire. Aggregate demand will falter causing disinflation or deflation. Investors compete for scarce Treasury securities, driving up their prices, thereby driving interest rates down. We saw this in the 2010s.

If the government spends more than what the private sector desires to save, that could be called expansionary or easy fiscal policy. Government spending fuels GDP, possibly in excess of its actual spending. Public deficits create private sector savings beyond what they desire to save. The private sector will react by increasing consumption and private investment. Treasury securities will decrease in value as a manifestation of that debt glut, which drives up interest rates. It’s possible (but not inevitable) that inflation will increase because government spending might drive aggregate demand beyond sustainable levels. We saw this in 2021 and 2022.

By now, it should be obvious how supremely important fiscal flows are for the economy in general, and asset prices in particular. Observing them and anticipating turning points and inflection points has tremendous potential for alpha creation.

It often feels like public deficit spending is in a continuous race to infinity. As the years pass by, media reports move from millions to billions to trillions. But beyond the headlines, deficit spending exhibits clear seasonal and cyclical patterns that are worth investigating. Let’s start with Seasonality.

Seasonality

The table below illustrates monthly Net Flows for the years 2006 to 2023. This is denominated in millions of dollars.

It’s optically immediately obvious that some months are stronger than others. There are a couple of reasons for that:

Interest expenses have become a huge fiscal flow driver. In FY23, they accounted for 40% of Net Flows and 10% of Gross Flows. This will probably increase significantly in the near-term because the effects of rising rates have not yet been fully digested. The current duration of the US Treasury portfolio is 6 years.

About 80% of the Treasury’s interest expenses happen on just 4 dates in the middle of each quarter: Feb 15, May 15, Aug 15 and Nov 15. On these dates, the Treasury injects north of $50bn into the economy.

Tax refunds typically happen in February, which makes that month particularly strong. When citizens know that they will likely get a refund, they will file as quickly as possible which typically happens in the first weeks of February. For the whole month, tax refunds often exceed $100bn.

Individual tax payments typically happen in April. When citizens know that they will likely have a tax liability, they typically postpone it to the last possible moment, which is typically in mid/late April. This is a massive fiscal drain that is often north of $200bn and that has often caused distinct dips in the stock market. Can you imagine where the term ‘Sell in May’ comes from?

Corporations typically pay their federal taxes on the 15th of the last month of each quarter, i.e. Apr 15, Jun 15, Sep 15 and Dec 15. In a typical quarter, these events drain about $80bn from the economy, which often coincides with market weakness. Sometimes corporations get extensions though. This year for example, due to natural disaster relief a large chunk of the September payment happened in October (how was the S&P’s performance this October?). It’s important to be aware of such distortions in order to avoid creating false signals.

Many other expenses don’t have annual, but monthly cycles. For example, social security payments happen pretty much every week with a peak late in the month.

Certain measures are worth tracking because they provide a general cross-read on the economy. For example, withheld individual taxes provide an excellent and timely insight into the state of the labor market. In fact, I believe there is no other metric more suitable to get information quickly should the labor market deteriorate. I will keep an eye on that.

Having established that there are seasonal Fiscal Flow highs (Feb, May, Aug, Nov) and lows (Apr, Jun, Sep, Dec), the key question is: How can that be incorporated into a trading or an investment strategy?

The initial urge may be to frontrun those flows. For example, buy before the February tax refunds and interest payments are redeployed. Or sell before the April tax payments are drained. I believe this is first level thinking though. Too easy. There are market mechanisms in place to avoid an exploitation of that. Markets frontrun these events. It’s therefore plausible that this frontrunning needs to be frontrun.

I will illustrate that with an example. Let’s look at the mid-quarter interest payment dates mentioned above. Instead of creating a pump when these happen, markets tend to create a top. Markets anticipate the redeployment of those interest payments and drive maximum pain for those investors receiving the interest payments. They make them buy higher.

The chart below plots the S&P against these quarterly interest payment dates. Quite often, local tops are very close to the payment date.

And markets tend to create bottoms on dates of fiscal drain to force investors with tax liabilities to liquidate at lower levels. There were distinct S&P bottoms in April 2022, 2018, 2017 and 2014. And outliers can often be explained easily. 2020 and 2021: Covid liquidity injections and low tax liabilities. 2019: Low tax liabilities because 2018 was a weak year for the stock market. Same for 2016.

It’s obviously not a perfect signal. Many factors come together at any given point in time to determine market moves. But it helps to be aware of these seasonal flows and I believe the case is strong that 2024 will start of strong into February and then show weakness into April. NFA of course. ;)

Cyclicality

Government spending is not just subject to seasonal swings, but also to cyclical swings, which are determined by exogenous shocks and shifts of political tides in conjunction with strength or weakness in the private sector. The table below shows monthly Net Flows for 2006 to 2023. To facilitate the visualization over longer time periods, I am not showing this in dollars, but as % of GDP.

Fiscal flows were very poor leading into the Financial Crisis. In many instances, they were in fact negative which means the government ran surpluses which drained savings from the private sector. In my opinion, this clearly foreshadowed the events that unfolded in 2008.

Starting in October 2008, flows improved sharply and remained like that in 2009 and 2010, which coincided with the rapid recovery that we say in the US stock market.

Afterwards, this strong initial fiscal impulse faded somewhat. Public perception is that the 2010s were extremely easy money times due to the Fed’s massive QE programs and ZIRP. But this is not true from a fiscal perspective. Sure, fiscal deficits remained high vs. historical benchmarks, but they came down a lot from crisis levels as tax receipts outpaced spending. I don’t think it is a stretch to argue that this timid public spending contributed to the stock market weakness in 2015 and 2016.

It’s also visible in the CPI which was below the 2% target for much of the mid 2010s.

A confused Fed tried to raise inflation with an extremely easy monetary policy. But it did not work because the driver was not that rates were too high. It was insufficient fiscal spending. Insufficient from a stock market perspective that is. I don’t have a political view what the deficit should be.

Overnight rate gymnastics mean nothing. Unless perhaps shifting wealth between savers and creditors. In our era, EVERYTHING is fiscal. The sooner you understand that, the stronger your edge against others will be.

2015 was the lowest point in that fiscal cycle with a deficit of $500bn for the year. Not too long afterwards, Trump entered the stage with his massive tax cuts. It propelled the deficit to almost $1tn by 2019. The S&P ended that year about 75% higher than where it begun 2016.

2020 and 2021 lifted deficit spending to a whole other level and we are all well aware of the consequences. 2022 was the hangover from that party. Enormous tax receipts drained a lot of liquidity from the private sector.

The robust 2023 stock market performance is in my opinion very much driven by the rebound in deficit spending. A rebound that is primarily driven by a) interest expenses from the Fed’s rate hikes and b) cyclically depressed tax receipts from the poor 2022 stock and bond market performance (arguably also driven by the Fed’s rate hikes).

It’s kind of ironic that this could even be construed as an argument that the Fed does in fact matter, unfortunately in a very different way vs. how it views itself and how it is perceived by market participants.

The bottom line of all of this is: Observing fiscal flows and anticipating seasonal/cyclical turning/inflection points therein can generate alpha. I am pumped to share my future findings with you.

Sincerely,

Your Fallacy Alarm

Surprised there are no comments yet. Please continue your hard work. Very enlightening.

Fiscal policy impact in the markets is not yet widely discussed, and your work provides a nice framework for it.

Is treasury debt issuance creating net savings if those buying bonds have less net cash? Or is the idea that those treasury securities can now be pledged for more borrowing or activities so there really is no change in their balance sheet situation?