The Great Vindication of Modern Monetary Theory?

If all economic activity starts with the public sector, then deficit spending is the only tool to manage inflation and employment. This would render the Fed's hiking campaign utterly pointless.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is an unorthodox way of economic thinking that contradicts many ideas of mainstream economics. It was actually introduced in the 1990s, but did not gain significant popularity before the late 2010s.

Lately, it has been scrutinized and even ridiculed a lot. This is presumably for two reasons. Firstly, it has unfortunately been hijacked by politicians as a theoretical justification for their agenda. This has created the impression that it is a partisan tool. Secondly, its opponents claim that the interest rate spike after 2021 renders the promises of MMT obsolete.

Both types of criticism miss the point. That’s a pity because MMT is actually a very curious way to think about macro. No other economic school of thought offers such compelling explanations for the confusing economic environment that we have to navigate these days. 18 months into the sharpest hiking cycle the US has ever seen, real growth stands at 5%. Without knowing about MMT, it is very challenging to make sense of this situation.

In this article, I will contextualize MMT into the mainstream economics landscape and I will articulate why it describes current economic events well and what that might mean going forward. I will also link MMT it into my macro framework that I have laid out over the past year because there are important overlaps.

This topic is not easy to digest, so I am offering an ‘At a Glance’ summary upfront before I go into the details later.

At a glance

MMT is a radical change from any other economic school of thought as it views the public (and not the private) sector as the beginning of all economic activity. It views monetary and fiscal policy as one entity. It postulates that all economic policy can be conducted with deficit spending. Rather than financing the government activities, it is a policy tool to manage inflation and employment.

It distinguishes between the issuer (public sector) and the user (private sector) of a currency. The former’s deficit is the latter’s surplus and vice versa. The central conclusion from that observation is that raising interest rates is stimulative because the issuer is a net interest payer. This enabled MMT to predict that the rate hikes would increase economic activity. No other school of thought was able to anticipate current economic growth 18 months into the sharpest hiking cycle ever.

Unfortunately, MMT has been hijacked by the political left and discredited by the right as a justification of overbearing centralism. That’s a pity because the key message of MMT is one that any economist would agree with: inflation is the limit to deficit spending. The pandemic stimulus was too strong, no MMT proponent would disagree with that.

Fiscal stimulus has become the dominating liquidity and bull market driver. Hiking to 5% and jacking up the entire yield curve in its slipstream was a political decision that the Treasury and the Fed made together (albeit not in conscious agreement). It has shifted wealth from debtors to creditors and it’s likely that it kept inflation higher for longer. If policymakers really wanted to fight inflation, they would lower rates and reduce deficit spending. So far there are not any signs for that which suggests the party will keep going for a while.

People’s biggest fear about the fiscal spending spree is that government debt will spiral out of control and become a burden for future generations. Taking the issuer vs. user perspective demonstrates that such fears are unfounded. In fact, it would be ironic but possibly true: A forceful continued fiscal impulse might over time reduce debt/GDP.

Let’s quickly browse through 200 years of economics first

Classical economics started with Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Their central idea was that free markets are self-regulating and the best thing from a policymaking perspective is to leave them alone. This idea came into doubt with the Great Depression of the 1930s which gave rise to Keynesian economics.

Keynes argued that the government can and should intervene with monetary and fiscal stimulus in times of crisis. This could reestablish trust and optimism which would shorten and weaken the downturn. This idea is closely related to the Phillips curve which was introduced as a model after Keynes died. The Phillips curve postulates that there is an inverse unemployment/inflation-relationship and the government can enact policies to choose any combination thereof that is deemed desirable. Keynesian economics was heavily scrutinized after the 1970s inflation spike as these tools either did not work or were not applied properly.

Monetarism emerged from that crisis and became the leading school of thought. It argued that Keynesian thinking leaves too much discretion to policymakers to make the right choice between stimulus and anti-stimulus. It postulated that policymakers should simply grow money supply at a constant rate with a rule based approach which would optimize economic growth and price stability.

This turned out to be very powerful to reestablish price stability in the 1980s, but it was very difficult manage monetary policy by targeting money supply growth because its short term relationship with inflation was quite unstable. Even the first Fed chair employing monetarist principles, Paul Volcker, abandoned money supply growth as his primary policy target by the mid 1980s.

That was pretty much the end of breakthroughs in mainstream economics. There were a few additional movements, but they merely regurgitated previous ideas. Austrian economics is a noteworthy example. It’s closely related to classical economics as it centers its analysis around the decisions and judgements of the individual arguing that economic order arises in a decentralized manner. But such ideas remained fringe. Most of the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s were characterized as a blend of monetarist and Keynesian ideas with an emphasis on the latter.

By the way, all of the economic schools of thought mentioned above have merit. There is no need to go tribal here. Each of them was born out of the challenges of its time to which it offered solutions.

What unites virtually all of them is that they start with the private sector. The economy is assumed to be primarily about citizens and corporations to interact with each other. They receive central bank money and use it for private money creation. The public sector then comes in as a second step as it is used for two purposes:

to redistribute wealth in a way that is deemed desirable to shift wealth around and

to smooth the business cycle to keep the economy close to its sustainable speed to avoid overheating (causing inflation) or excessive cooling (causing unemployment).

As the public sector and its share in the economy has grown tremendously over the past decades, this private sector focus gets somewhat diluted. There are some important new dynamics which require new ideas.

Enter: MMT

MMT goes the exact other way. It starts with the public sector by arguing that the US government and its agents (the Fed and commercial banks) are the sole supplier of US Dollars which is also the only currency it accepts as tax payments. That means all economic activity denominated in US Dollars starts with public deficit spending.

In order for the government to collect taxes from their citizens in the form of US Dollars, it must first supply them with these Dollars by buying goods, services or assets from them.

This has important ramifications, some of which are conflicting with traditional ideas in economics:

The government can manage the business cycle by increasing deficit spending which is expansionary or decreasing it which is contractionary. They can do so by massaging outlays (spending more or less) or receipts (taxing more or less). If you think about the United States as a corporation, US Dollars are its shares outstanding. They can make them scarcer by retracting them or less scarce by printing them into circulation.

Deficit spending is first and foremost an economic policy tool that has nothing to do with the government living its means or not. In contrast to a private household, the government cannot run out of money. They can simply print the money needed via its agents.

The limitation for deficit spending is therefore not access to capital but occurrence of inflation. Once inflation exceeds desirable levels, the government must reduce outlays or increase receipts. Historically, periods of sub 2% inflation are therefore times of overly tight fiscal conditions. Much of the 2010s were such periods. According to MMT, much of the 2010s was in fact austere. A stark contrast to what an Austrian economist would tell you.

The public sector does not compete with the private sector for debt. Therefore there cannot be a crowding out effect that would manifest itself via driving interest rates above sustainable levels. MMT asserts that it is in fact the opposite. Public borrowing supplies the base currency needed to enable private borrowing. It greases the economic chain.

The government is a net payer of interest. Higher interest rates are therefore stimulative and expansionary. Lower rates reduce demand and are deflationary. This driver is particularly relevant if public debt is large as a % of GDP.

The public sector deficit is the private sector surplus and vice versa. The government can only collect US Dollars as taxes if it has issued them before via deficits. They can never collect more in taxes than they have previously incurred as budget deficits. That’s why a public deficit is the normal condition and public sector surpluses are actually abnormal exceptions that should only happen temporarily when the economy runs overly hot. The private sector surplus includes the domestic private sector and the foreign public and private sectors. A foreign sector surplus is also known as a trade deficit. Therefore, deficit spending enables other countries to satisfy their wish to save/invest in the US.

MMT has some overlap with traditional economics, most importantly Keynesian ideas. It also proposes to manage the business cycle with stimulus. But it’s a radical change in thinking economic policy in that it completely ignores monetary policy as a separate entity. It’s views central banks merely as agents of fiscal policy. Warren Mosler even goes as far as proposing that the natural overnight rate is simply zero.

His logic flows like this: As a monopolist, the currency issuer can freely set the price. The price of a currency is its interest rate. By choosing a rate greater than zero, the currency issuer subsidizes those entities that have overnight accounts with the central bank, namely commercial banks. Mosler believes that this subsidy is unnecessary and proposes to end this by setting overnight rates to zero. He argues that inflation can be managed with fiscal methods alone.

Under pure MMT, there would not be any government interest rates with longer tenors. Since the Fed would effectively merge with the Treasury, the deficit would not be financed with treasury securities, but with deposits directly credited to the accounts of entities selling goods, services and assets to the government. For example, if the government wanted to pay a government employee, they would not issue treasury securities, but instead simply credit his bank account with a deposit.

What follows from here is that jacking up the entire yield curve was a political choice that the Treasury and the Fed made together (albeit in conscious agreement) to shift wealth from debtors to creditors with the byproduct of keeping inflation higher for longer. Fighting inflation would be much more effective with low rates and a reduction in deficit spending. MMT or not, the more I study this topic the more I am convinced that this is true.

The partisan nature of MMT

One of MMT’s first proponents, Warren Mosler, was originally a hedge fund manager and entrepreneur who later moved into academia. Today, he does have economic policy recommendations, but it does not seem that his original objective was to drive political change. He wanted to use his macro research to make money.

However, over time, MMT became closely associated with the political left in the US. For example, Stephanie Kelton is an important current MMT proponent and used to work as an advisor to Bernie Sanders. She wrote The Deficit Myth which became very popular in 2020.

By arguing that deficit spending is first and foremost a policy tool to manage the business cycle, MMT asserts that it has nothing to do with living your means or not. It rejects the idea that deficit spending leaves a ton of debt to your children. This dramatically changes the perception of deficit spending from being a nasty and unethical thing to something that is actually desirable and normal.

That conclusion can be exploited by centralists. It empowers those people who want the government to have more power. Naturally, such an idea is highly popular on the left and highly unpopular on the right. Stephanie Kelton openly demands more public spending in her book and paints heavy deficit spending legitimized via MMT as a tool to overcome social issues.

I can imagine that taking such a normative stance helped her winning over mainstream literature and made her book a bestseller. But in my view, it doesn’t do a favor to the academic ambition of MMT, which is about using MMT to understand and anticipate economic processes.

One of MMT’s central messages is in fact one that no economist would dispute: The limit to deficit spending is inflation. Kelton acknowledges that very early in her book:

“Just because there are no financial constraints on the federal budget doesn’t mean there aren’t real limits to what the government can (and should) do. Every economy has its own internal speed limit, regulated by the availability of out real productive resources.”

Stephanie Kelton, The Deficit Myth

MMT is precisely not the tool for an endless spending spree that its opponents claim it to be. But very few people actually spend time fully understanding an idea. So, MMT has become for the left what Austrian economics has been for a while to the right: a theoretical foundation to justify political positions.

While MMT is about centralized order, Austrian economics argues that the best footing for order is in a decentralized manner by relying on the interactions and judgements of empowered individuals. If you want to divide all economic schools of thought into two groups you could put classical, monetarist and Austrian economics on the right and Keynesian and MMT economics on the left.

The overlap between MMT and Fallacy Alarm

There are important overlaps between MMT and the economic ideas I have posted this year.

As a quick summary:

From a macro perspective, my main talking point this year has been that fiscal stimulus has replaced monetary stimulus as a primary bull market driver. Some people call that fiscal dominance, I call it the age of governmentism.

Liquidity drives asset prices and it has to be viewed much more comprehensively than just looking at what the government arbitrarily defines as money supply. It includes all credit/debt outstanding that is in private sector hands, irrespective of the issuer and its duration. It includes claims against central banks (coins, bank notes), commercial banks (deposits), governments (most importantly treasury securities) and companies (corporate bonds).

Any additional piece of debt becomes a financial asset that greases the economic chain and becomes a yardstick for asset prices. Newly issued debt does not compete with equities for investor money. Investors don’t buy it by selling stocks (at progressively lower prices). Additional debt raises the collateral against which all other asset prices are measured.

With its unprecedented tightening campaign, the Fed is trying to reign in liquidity. But by definition, this only works for interest rate sensitive liquidity, i.e. private sector debt. The biggest liquidity driver is public sector debt which in fact has a reverse sensitivity to interest rates. Higher rates, higher deficit, more liquidity.

Fiscal stimulus and monetary stimulus are very similar with a few distinct nuances. The most important nuance is that the arrival of a fiscal liquidity impulse raises interest rates while the arrival of a monetary liquidity impulse drops them. We are used to associate liquidity with falling rates. This is why many people get this impulse wrong.

Aside from the carnage in the bond market (that I have warned about all year long), high rates are therefore not necessarily a problem for risk assets.

MMT makes an important distinction between currency user and currency issuer. Therefore, it would never put private debt and public debt into the same bucket like I have done above. But it is in fact similar to my ideas as it has identified that public debt issuance is the dominating liquidity force in the economy, particularly during a time of sky-high public debt levels.

MMT also recognizes like I do that rising interest rates are in fact stimulating in an economy where the government is an important net interest payer. I called this the Double Flywheel of Treasury Yields in my Ten Trillion Dollars article. They call it the interest income channel.

Warren Mosler has argued for a long time that raising rates will be stimulating and in fact fueling inflation. He did this for example in this interview in mid 2021, almost a year before the hiking cycle started.

When people say that MMT failed in 2022 because deficit spending ignited inflation and caused the interest rate shock, they get the story completely wrong. After all, the central message of MMT is that inflation is the limiting factor to deficit spending. The pandemic stimulus was too big and therefore it caused inflation. I am sure any MMT proponent would agree with that.

And with respect to the aftermath of that mess: And it is absolutely possible that inflation would be lower by now if rates were lower because rising rates are increasing the deficit, which increases the private sector surplus, which increases inflation. My plan was to quantify that here for you, but I realized it would overburden this article. I’ll save it for a future one.

MMT and QE

About a decade ago, there was an interesting debate between Mosler and Bob Murphy, a proponent of Austrian economics. Towards the end of the debate, the moderator allowed them to challenge each other with three questions. As one of them, Mosler asked Murphy about the mechanism with which the large post GFC QE programs would create inflation.

He did not get a useful answer and unfortunately the moderator did not follow up with Murphy on that. Because this is in fact a central point.

As I have articulated in this article, when the Fed buys Treasury securities, they expand their balance sheet which is deemed to be expansionary. But in fact, they simply drive an asset swap in the balance sheet of the commercial bank that acts as their counterparty. This bank will have less securities and more cash assets.

The Fed hopes that having more cash assets will incline the bank to use that money for economic activities such as lending. But if the bank does not do that (because it does not want to or is not able to), there will be no material real economy liquidity impacts. It's liquidity that remains dormant in the Fed. And look how much it has become:

If the private sector is on a liquidity strike, the only way force liquidity into the economy is via deficit spending. MMT has understood that, Austrian economics seemingly not.

But can they really not run out of money?

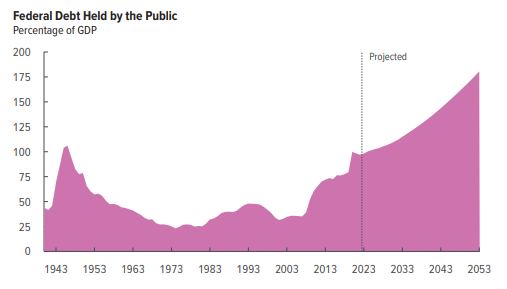

The chart that spooks most people is this:

Per the Congressional Budget Office, federal debt as a % of GDP is projected to rise to 180% over the next 30 years. If rates stay at 5%, that means interest expenses will amount to 9% of GDP. If you interpret this in a traditional sense, it means that almost $1 out of every $10 we earn must be used to pay interest by the government for debt it raised in our name.

Distinguishing between the user and the issuer of a currency is possibly the greatest leap achieved by MMT. So far, I always looked at the government taking on debt in the name of us citizens. And I can imagine you have done so as well.

MMT’s approach is a radical change. It views the government as a separate entity. Think about it like a corporation with the mandate to govern a country, set and enforce the law and provide citizens with the legal and physical infrastructure to live their lives. To accomplish this goal, the government issues US Dollars which become the standard unit of account for the citizens living within its borders.

But what if we did not measure our grocery bills and our bank account statements in US Dollars? What if we measured them in equivalents of Apple shares? If Apple paid their employees exclusively in Apple shares and raised their salaries, then a lot more Apple shares would be floating around. With an unchanged number of goods, services and other assets, the prices of those as denominated in equivalents of Apple shares would rise, a phenomenon that is widely known as inflation.

In such an economy, GDP is measured in the amount of goods and services exchanged denominated in equivalents of Apple shares. The ratio of the number of outstanding Apple shares to GDP is utterly irrelevant for Apple.

If interest expenses really rise to 9% of GDP, imagine how insanely inflationary this would be. The interest income channel would outweigh traditional monetary policy channels by far. It would be completely illogical not to monetize the debt at that point.

I believe the runaway public debt boogeyman is a phantom. It’s a threat that does not exist. Look at the chart below. Despite enormous deficits, Debt/GDP has been trending down over the past three years:

The crux is this: Either excessive deficit spending causes inflation or it doesn’t.

If it does then nominal GDP will grow, possibly faster than the debt. We have seen that in the 1950s that melted away the World War II debt.

If it does not, there is no need to keep rates high and there is no limit monetization of public debt via central bank operations. We have seen that in the 2010s. And as illustrated above, much of the 2010s came with inflation below the 2% target which suggests that fiscal spending was too low during that time. Perhaps that is the reason why Debt/GDP climbed? It would ironic but it’s possible: A powerful fiscal impulse can eventually reign in Debt/GDP.

Sincerely,

Your Fallacy Alarm

#2 what is "deficit spending"? It is nonsense. You cannot spend a deficit. You cannot spend by having a deficit, nor by not having a deficit. Governments running MMT systems (most of them) spend in one and only one way, by instructing their central bank to mark up bank accounts, using a computer. No deficit is involved.

The government surplus/deficit is an accounting residual you only know at the end of an accounting period. If full employment has been achieved no one should care what the number is, positive or negative. That they *do* care is a cause of massive economic misery for the poor.

Needs a bit of editing: e.g, #1

"It postulates that all economic policy can be conducted with deficit spending. "

not really. You've got to drive demand for the 'otherwise worthless' currency, so at an absolute bare minimum MMT tells you you've got to tax or impose fines or something, in the currency only you (Gov) can issue, or lend via agent commercial banks (chartered by the state). So it is Fiscal Policy that achieves monetary economic goals, and no other goals per se (real production is the aim, but via rampant corruption and rentiers not always realised).