Wirtschaftswunder in Reverse

The Downfall of Germany: bankrupt pension system, end of ICE age & mismanaged energy policy.

When people ask me why I came to Canada, I usually tell them that my wife imported me here. After the initial chuckle, I tell them it was a great opportunity for me to broaden my horizon. Growing up, I always wanted to live abroad for some time. You learn a lot about another culture. And as a byproduct about your own.

But there is another reason I usually don’t talk about much. We also chose Canada over Germany for our two young boys. Canada has its own challenges, but generally it feels like a much better bet for the coming decades. When I do mention this to locals, it sounds absurd in their ears. After all, Germany still has the aura of an economic powerhouse. Great engineering, great work ethic, political stability. Unfortunately, I believe this perception is mostly based on a brand built in the past, which is currently being demolished by delusional politicians mismanaging a challenging demographic setup and structural changes in the economy. Observing my country being on the wrong path gives me heartache and there are many aspects that I would like to share with you. To not overburden this article, I have decided to focus on the three most pressing issues for now:

The bankrupt pension system

The end of the ICE (internal combustion engine) age

The failed renewable energy transition

1. The bankrupt pension system

„Kinder kriegen die Leute immer“ (“People will always have children”)

Konrad Adenauer, 1957

The German public pension system is called Allgemeine Rentenversicherung (ARV). It had existed since 1889. But the current system is primarily based on a big reform in 1957. This was necessary because WWII had effectively stopped it from working properly. Per the 1957 reform, it was decided that pensions will:

Grow with wages

Fully replace wages in retirement (rather than being side money for the retiree)

Be financed out of current contributions

No matter from where in the world you are reading these lines, when you think about your pension plan - whether it is public or private - you probably think about something like a defined benefit plan. You contribute money into it over time and the carrier (for example your employer, the government or an insurance company) guarantees you a certain payout profile when time comes. The best case would be that the carrier keeps this plan funded, i.e. the present value of the pension payments does not exceed the plan assets. Sometimes, plans become underfunded, which means the carrier will need to somewhat subsidize the plan in the future.

The ARV is not funded or underfunded. It is UNFUNDED.

At any given point in time, there are no more than 1-2 monthly payments on the ARV balance sheet in cash. This means that a €1 contribution paid by an employee into the ARV in January will be used to pay a retiree €1 in February at the latest.

Now, this would not be a problem if the population structure was stable. There are even people cheering this unfunded system for its resilience in times of market turmoil. Don’t have money, can’t lose money. Celebrating to be broke. Fantastic logic, isn’t it?

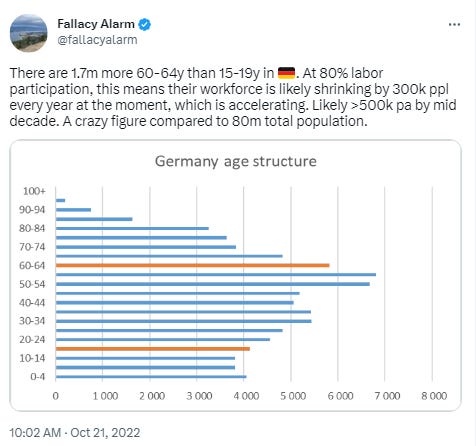

Unfortunately, the German population structure is not stable at all. Too few people entering working ages, too many exiting working ages. In the coming years, 500k people more will retire than start working. More than 1% of the work force. Every single year.

Consequently, dependency ratios are rising rapidly. Compared to other large economies, this ratio is actually not that bad at the moment. But that will change this decade.

The age structure globally and in Germany in particular is flipping upside down in a dramatic fashion. This is something that the 1957 policymakers were not able to anticipate.

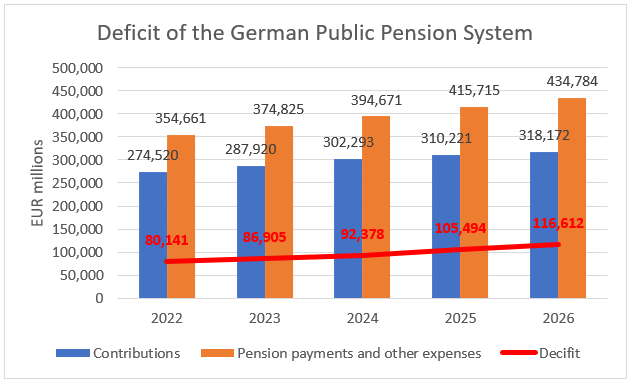

And the public pension system is overwhelmed. The table below shows the 2022 actual and 2023-2026 projected income and expenses for the ARV per the 2022 pension report of the federal government.

As you can see, it currently operates at a €87bn annual deficit. By 2026, this deficit is expected to grow to €117bn. A structural deficit increase of €30bn in just three years. This deficit is tax payer funded.

So, where does the funding come from?

The table below shows Germany’s 2023 federal budget:

The government plans to spend €476bn and earn €389bn, which equates to an €87bn deficit (2.2% of GDP). Unfortunately, this is not complete because the German government is pulling all kinds of tricks to disguise the true scale of their spending binge.

Their preferred tool is the implementation of so called Sondervermoegen, which translates to special purpose funds. This label is almost criminal. The German term (even more than the English translation) indicates that there is equity here, which is not the case. The truth is that these Sondervermoegen raise debt in the name of the German people and then spend this in line with the purpose they were created for. Sonderschulden (special purpose debt) would be the better term and it should be part of the official budget obviously.

The most important ones include WSF Energie (energy subsidies in conjunction with the Russia-Ukraine conflict), KTF (climate related investments) and Bundeswehr (additional military spending). As a result, the true total budget expenses amount to at least €642bn, which equates to a €253bn deficit (6.5% of GDP).

As highlighted above in yellow, the tax funded pension subsidies amount to €112bn. This does not fully reconcile with the €87bn deficit noted before because the government also provides regular pension benefits on top of balancing the deficit. These benefits include for example contributions for parental leave. At the end of the day it does not matter whether a government payment to the pension system is based on regular scheduled support or irregular deficit support. Ultimately, it needs to be paid for by the wage earners. Since their contributions are insufficient to keep the pension system running, a part of their taxes needs to be used. How much?

Coincidentally, the €112bn almost perfectly lines up with the entire €110bn budgeted income taxes on wages.

~100%! The entire proceeds from income taxes on wages are necessary to keep the pension system afloat.

This would not be a problem if the sum of taxes and pension contributions were reasonable. After all, as an employee you do not really care what your deductions are used for. You simply want as little of them as possible.

So, how much are Germans paying?

The table below shows an illustrative payslip of a German employee who does not have kids and earns €80k. His actual true gross salary is €94k because the employer pays for some of the social security deductions directly. Think of this like an attempt of the government to hide the true amount of the deductions.

His total deductions amount to 49%. He only takes home a little more than half of his gross salary. Federal taxes and pension payments account for together 24% or €22k1.

I really want to drive this point home because it is so important: If someone makes €94k, he effectively pays €22k into the pension system, which will not go into investments earmarked for his retirement, but instead straight into the bank accounts of current retirees. And this is just before the biggest retirement wave in the history of the republic.